Most People are Other People

This body of work was exhibited at two venues in London - the National Portrait Gallery and the National Theatre.

MAKING PORTRAITS OF ACTORS

by Stuart Pearson Wright

So why choose to paint and draw actors?

In embarking on this collection of drawings, my purpose was to work out why? At the heart of it is a fascination with the idea of artifice: one thing pretending to be another, from the chance observation of a lady applying make up on an underground train, to the Technicolor excesses of Stanley Donen’s Singing in the Rain. Common to these phenomena is the wilful suspension of disbelief. We know that the lady on the underground’s mask is not real. She is sitting there with her lipstick and yet we allow our disbelief to be suspended and humour the fiction. Moreover, we enjoy fiction. We take great pleasure in seeing the work of the clever magician or draughtsman, anyone really who can convince our eyes that we are seeing something real whilst our brains know it is an illusion. There is a kind of delight in this paradox. Actors are fascinating for similar reasons. We are presented with the appearance of human emotion and conflict, and yet beneath the drama exists the reality of the actor.

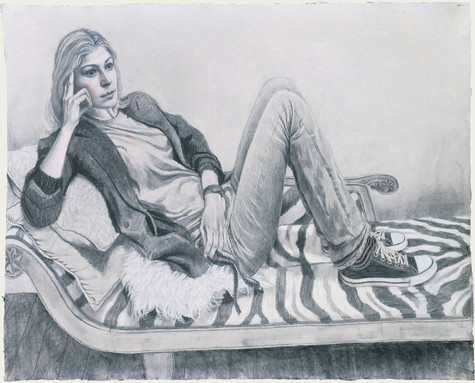

What is revealed when the portrait artist is faced with the actor who is without costume and make up? Implicit in this question is the suggestion that the actor has a fixed identity, an essence or sense of character that the perceptive artist can contain in a portrait. For my part this idea is unsustainable. At best the draughtsman can capture something of the mood of their subject but even this can be entirely misleading. Observers make numerous assumptions about a person’s character based on their portrait. But how can we honestly know whether an expression reveals profound melancholy, a searching and contemplative mind or else simply a case of constipation? The point of all of this is that identity itself is a chimera, something that is fluid and ultimately unknowable. We are all searching for a sense of identity. Actors fascinate me because they change identity before our eyes and we conspire to believe the fictions we are presented with.

But the actor only does in a formalised way what the rest of us do through being human. Most people are other people, playing out their daily lives in character, continually developing and tweaking a range of personas suited to every occasion. I would like to believe in the idea of a soul but find that I can’t. I am aware of the irony of this, as someone who makes portraits - the mythology of portraiture being the revelation of the soul through the artist’s hand and eye. I will have none of this. In my view when we die - we’re dead. Nothing leaves the body except perhaps for gasses and faecal matter. And so when I look at a person who sits for me, what I see is a very complex genetic organism with a whole set of dispositions determined by DNA and other factors - but beyond that - a kind of vessel in search of a sense of self, an identity. From observing one’s parents and peers, snippets of Eastenders, conversations on buses, characters in novels and movies - we are endeavouring to construct characters that feel authentic. We are inventing ourselves. But it is nearly impossible for people to be authentic when the language of our actions is so referential. Oscar Wilde said: “Being Natural is only a pose and the most irritating one I know.” Humans cannot be natural; we must leave that to the rabbit shitting in the forest or the spider in its web catching flies.

Of course, it could be that I am simply projecting my own existential anxieties upon my sitters. Maybe they do all have souls and there is a God after all - in which case I will have to eat my words.

OUT OF CHARACTER?

by Robert Meyrick, Head of Art University of Aberystwyth

Portraits hold a special interest for us because they are about people; they are personal records of others made public for our scrutiny. We know there are drawbacks to analysing faces and body language to learn about an individual’s personality; but that does not deter us from observing the person standing at a supermarket checkout, or sitting at an adjacent restaurant table, as we ponder clues of character. The Bard himself observed that “there is no art to find the mind’s construction in the face” – yet who could resist an art that seems to promise no less.

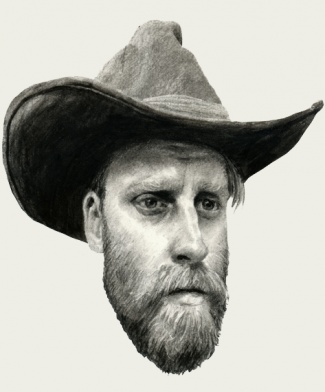

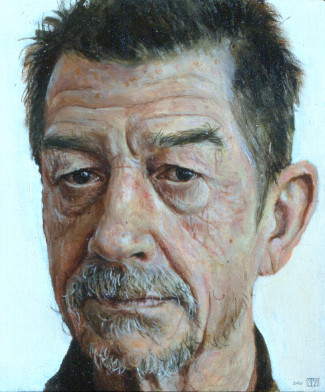

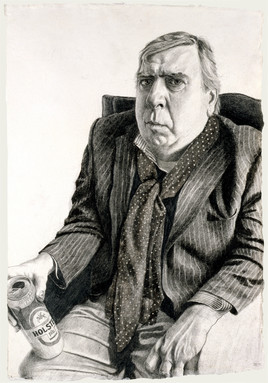

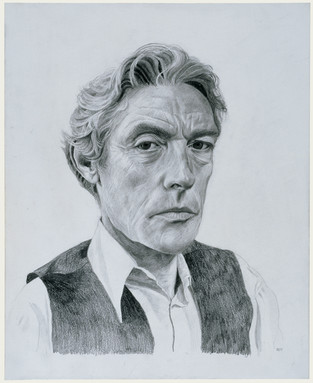

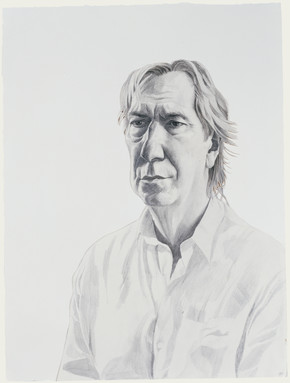

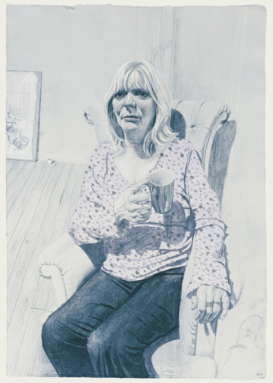

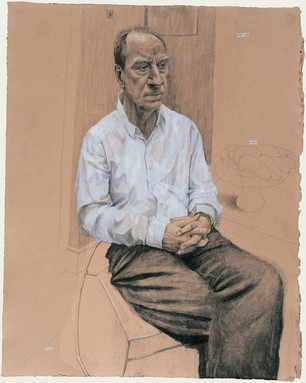

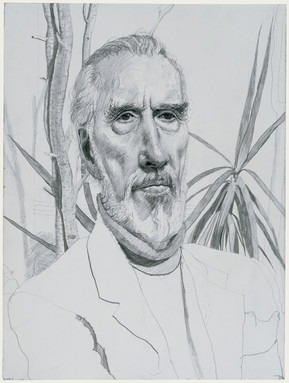

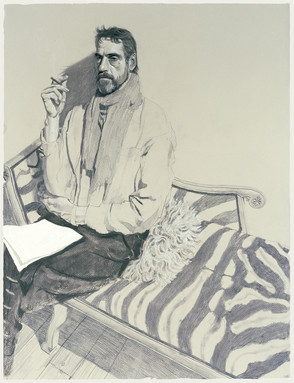

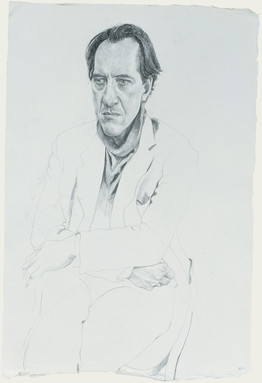

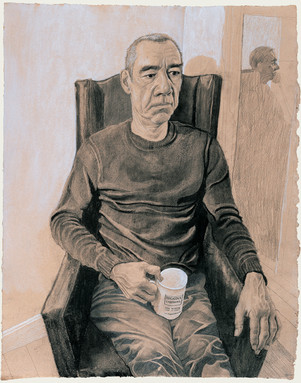

We are intrigued and tempted then to look at Stuart Pearson Wright’s new drawings of familiar personalities of the stage and screen, to interpret each gesture or expression for some sign of what these people might really be like, out of character. But on or offstage, what’s the difference? Jeremy Irons, appearing deep in thought, a script on his knee, or Timothy Spall posing with lager can, is no less a construct than William Hogarth’s flamboyant 1745 portrait of the actor David Garrick performing as Richard III. Oliver Goldsmith remarked of Garrick at the time that “On the stage he was simple, natural, affecting; / ’Twas only when he was off he was acting”.

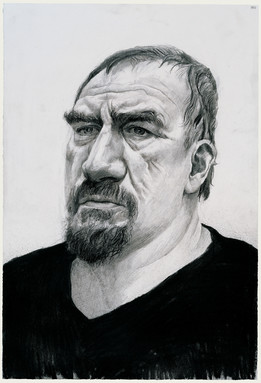

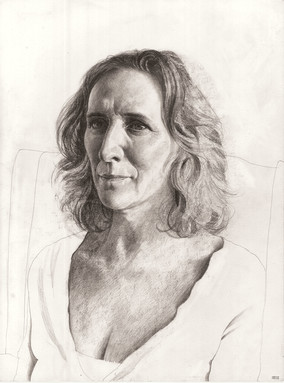

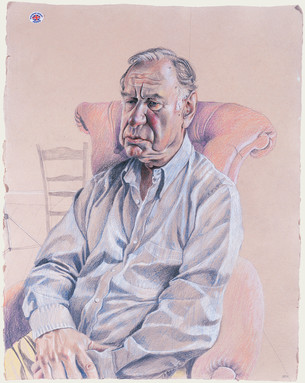

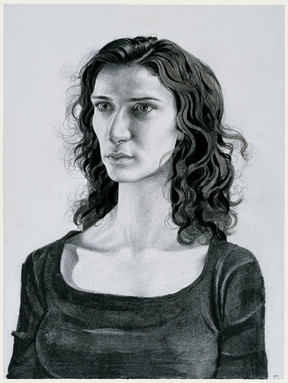

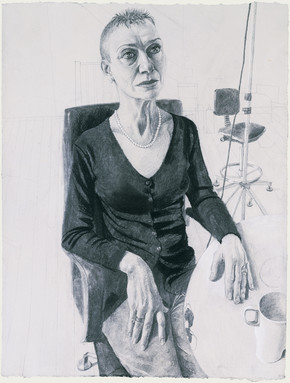

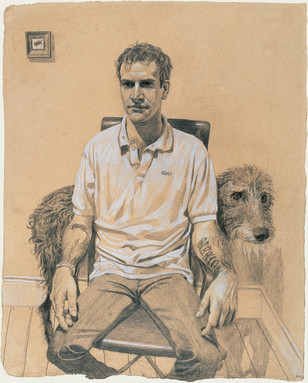

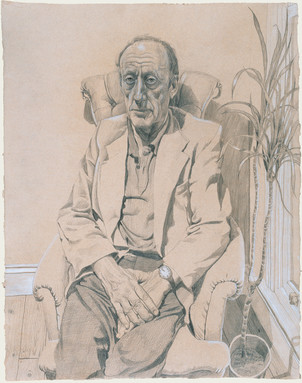

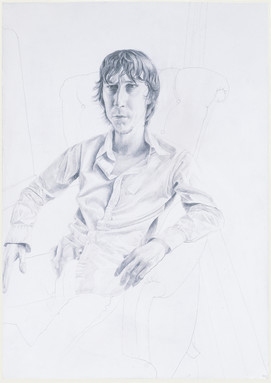

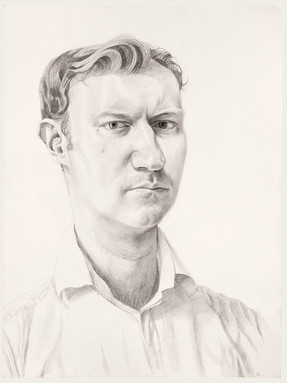

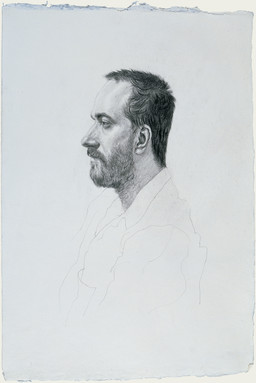

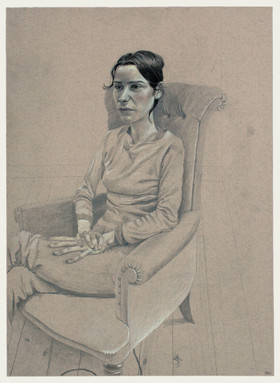

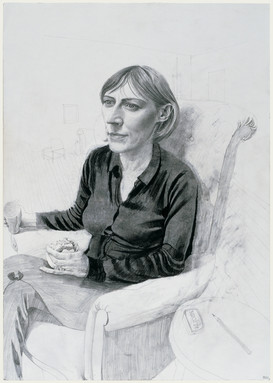

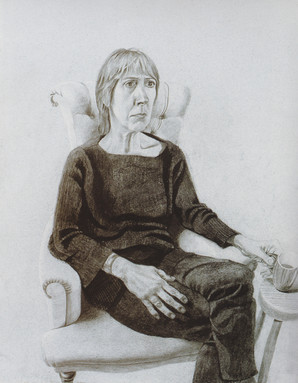

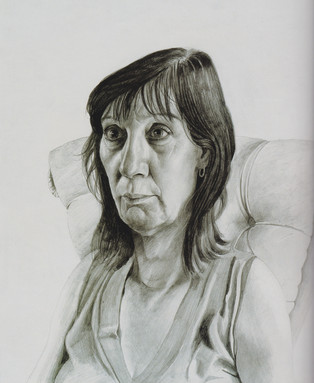

Despite their small scale and intimacy, these drawings can tell us as much, if not more, about the artist and the subject than the grandest of oil paintings. In the sensitive and searching portrait of Siân Phillips, attention is directed to an expressive face by understatement elsewhere. The sitter’s face, close to the picture plane, forcibly engages the viewer, holding our gaze well beyond the initial moment of recognition.

Here is an exhibition we are delighted to host at the University of Wales, Aberystwyth. We are fortunate in Stuart Pearson Wright to have an artist of conviction, one with consummate skill and integrity who, for young art students, is an excellent model of a contemporary artist whose practice is founded upon good craftsmanship and technique, and informed by the great tradition of European painting and drawing, yet peculiarly his own. A keen draughtsman, he is preoccupied with graphic artifice, the conventions of picture making and the language of drawing. One of our most versatile portrait artists, Wright pursues his objective with veracity and little regard for passing trends: a sincere and original contribution in itself.

PORTRAITS OF ACTORS BY STUART PEARSON WRIGHT

by Sarah Howgate

My first encounter with Stuart Pearson Wright’s work was in the form of the now infamous ‘dead chicken’ painting that won first prize in the 2001 BP Portrait Award. It was clear then that this was an artist to note - a portrait artist with bite. Four years on, with this new body of work about to go on display at the National Portrait Gallery, there is no doubt that Stuart has lived up to early expectations.

Gallus gallus with Still Life and Presidents (2001), the controversial group portrait of the six former presidents of the British Academy had all the characteristics of future works. An exquisitely executed painting with more than a nod to the Flemish old masters, this commission was a challenging assignment. To paint a meeting of these senior figures in a boardroom setting had the potential in another’s hands to be rather staid but the resulting work proved to be anything but conservative: both masterly and contemporary, as well as slightly unnerving and surreal.

Stuart was characteristically outspoken in the publicity surrounding his prize-winning portrait, raising more than a few heckles and perhaps burning a few bridges. With a confident and at times eccentric demeanour, coupled with an ambition and artistic accomplishment beyond his years, Stuart has continued to be a high-profile artist on the portrait scene ever since. In 2002 his unconventional portrait of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, originally for the Royal Society of Arts, depicted Prince Philip with a bluebottle on his naked shoulder and a cress plant growing from his forefinger. The painting provoked the headlining comment from his subject: ‘Gadzooks’.

In 2005 Stuart delivered a paper at the National Portrait Gallery on contemporary portrait painting, which was challenging and controversial. In the lecture he admitted that he felt his portrait of Prince Philip was a failure because it lacked empathy and lapsed into caricature. Declaring much of contemporary portraiture tedious because it focuses on simply illustrating a person’s likeness, he went on to praise the work of Lucian Freud and the younger portrait painters, Justin Mortimer and Philip Hale. In Stuart’s opinion the success of any contemporary portrait relies on its relevance to the time in which we live. “Portraits need to respond honestly and intelligently to what it means to be human, not to represent ourselves as filtered through the outmoded concerns of past cultures.”

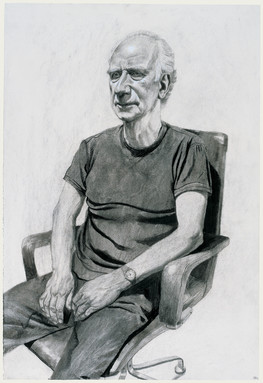

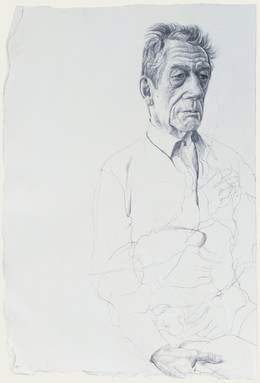

As the winner of the BP Portrait Award, Stuart was to be considered for a portrait commission for the National Portrait Gallery. Trying to persuade an eminent subject to sit to Stuart was no mean feat. First of all Stuart’s sittings are demanding and lengthy – the former director of the National Portrait Gallery, Charles Saumarez Smith, who sat for his own portrait, can attest to that. Stuart’s stigmatism also means that he insists on his subjects sitting at uncomfortably close proximity. This particular way of seeing also leads to an elongating of his subjects, that is not always flattering. Stuart distorts the subject’s features or plays with the perspective of space to undermine the illusion of reality in order to create, in his words, a ‘distancing effect’.

After more than a few false discussions with subjects who simply could not face the rigours of sitting to Stuart, the internationally acclaimed children’s writer, J.K. Rowling, was willing to make the imaginative leap of faith. In some ways this was surprising - Rowling is famously shy and guards her privacy closely. However, she was intrigued by the dark humour in his work. With this shared creative vision, Stuart and Jo hit it off. The resulting three-dimensional trompe l’oeil portrait is appropriately unexpected, otherworldly and surreal. It also offers an empathetic glimpse into the private and at times isolated world of a writer. Stuart has cited influences from Dürer to the early works of David Hockney (who in turn is an admirer of the younger artist’s work), and the painting has proved to be a popular addition to the contemporary collection at the National Portrait Gallery.

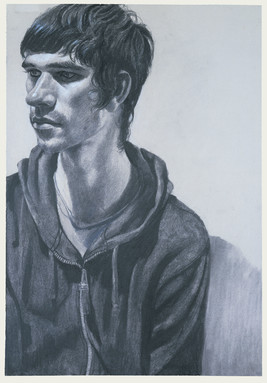

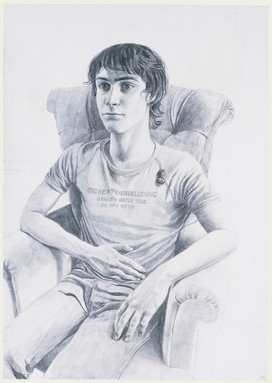

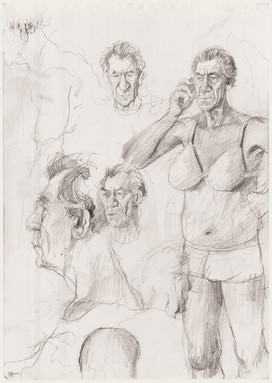

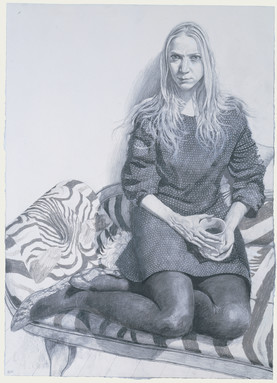

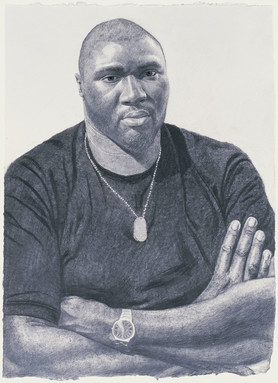

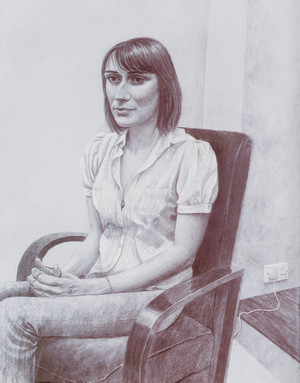

Stuart first approached the Gallery with the idea of this display of portrait drawings of actors some time ago. Initially we were more concerned about seeing the commissioned portrait of J.K. Rowling completed and suggested he put the other project on hold. Unbowed, Stuart continued with the work in tandem. Most people are other people is a project that reveals his tenacity of spirit. He is not shy about approaching actors and for the most part actors are not shy about sitting. However, finding the time between performances is often problematic and a certain amount of opportunism and flexibility is required on the part of the artist. The challenge is to capture the actor with his or her guard down, as themselves rather than the character they are about to perform. This is demanding on the artist and requires a mutual trust.

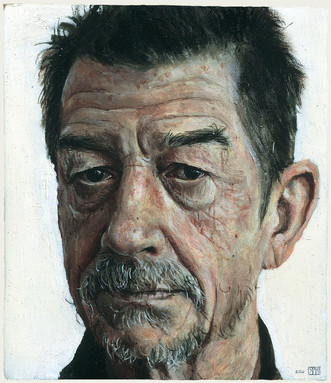

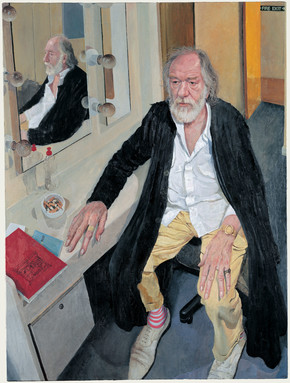

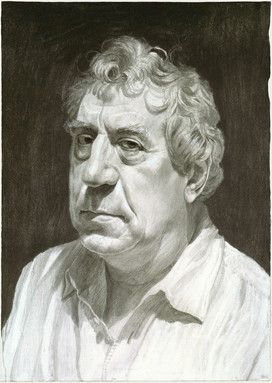

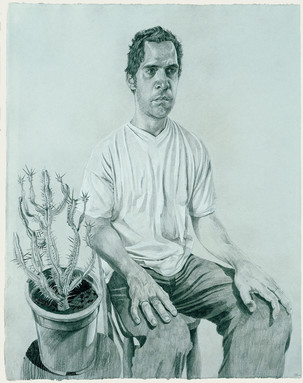

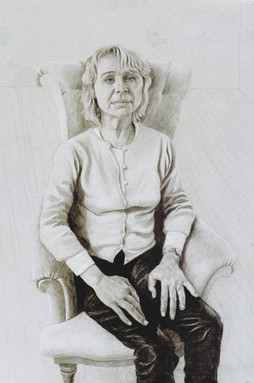

Stuart had already demonstrated his skill at capturing actors with his portrait of John Hurt appearing in Beckett’s Krapp's Last Tape in the National Portrait Gallery collection. The painting came about because the artist approached the actor when he recognized him on a Soho street. Although Hurt was initially rather taken aback, he responded to his request and agreed to sit. Stuart has a love of the theatre. Had he not been an artist, he would have pursued an acting career. He certainly has a sense of performance and the theatrical. (For the unveiling of the J.K. Rowling portrait he appeared dressed like a fin de siecle dandy.) This new series of drawings reveals a sensitivity and insight into the actor’s lot. There is a moving vulnerability in each of the portraits that is painfully true to life. In these images he captures a moment back-stage but the whole of theatre is there. His subjects often appear haggard, their faces revealing the rigours of hours under the spotlight. They are also treated masterfully, each one beautifully drawn in painstaking detail. The cast of characters represents a cross-section of actors from the Royal Shakespeare Company to soap stars, male and female, young and old, celebrities and emerging figures. Although these drawings share a similar format, one is struck by the individuality of each subject. Without resorting to caricature, they are instantly recognizable. They are also a promise of what is to come.

There is something wonderful about the very particular intimacy of a set of portrait sittings. It is difficult not to grow extremely fond of whoever one is drawing or painting. Scrutiny demands empathy and empathy leads to affection. The longer I stare at a person the greater the sense of empathy and the stronger the affection.

January 2006

ALL ACTOTS WANT TO BE ROCK STARS AND VICE VERSA

by John Hurt

In Stuart Pearson Wright’s case, here is a painter who would like to be an actor – and indeed, why not, it is a shame that the renaissance gave way to the specialisation of the modern world. However the idea of Stuart Pearson Wright switching to an acting career would seem absurd.

It is the reason for such a switch seeming absurd that interests me, for it is because he is so obviously and clearly gifted as a painter that to deny or neglect such a gift would be worse than absurd – it would be criminal. In a world where celebrity without reason and artistry without craft are acceptable, it is refreshing that one senses stirrings of indignation at the idea of such a gift going to waste.

When content is harnessed with form, so much more powerful is the result.

Text by an anonymous actor

It's just a film. I have created the whole thing. It's all happening in my head.

And so I've decided I've just got to forget about it, forget about him,

because this week I've really felt like I'm losing my mind.And I'm not being

dramatic. This is why. Because I've created this fucking obsession, and

everything else in the world feels like it's been created too. Nothing feels

real. What I thought was real was just fantasy and there's nothing underneath.

It's all empty. I'm not a poet so I can't really explain what I mean but

my thoughts have been taking weird spirals all week. I think this is always

the danger in creating something. If you can create something so vividly

that it becomes real for you then how do you keep a hold of what is

actually real? How can you draw the line? Suddenly nothing is real and

everything is an invention.

2005

...by Michael Gambon

It's just a compulsion. They have this built-in desire to be somebody else. Actors are show-offs, bigheaded bastards, egomaniacs. I can't think of any other reason they act.

STUART PEARSON WRIGHT

In conversation with Timothy Spall

SPW What was that you said? You were asking about your portrait?

TS I said, was the drawing you did of me any good?

SPW I think it’s one of the best in the series.

TS Oh good. It’s only fortunate that I was in such deep pain with the alcohol, that you caught an expression of fear and sensitivity in my eyes

(they laugh)

TS I got better though, you drew the foul unctuous waters out of me.

SPW I had this extended argument with a lady and she was saying that I had an ability to capture the soul of the sitter. I was contesting that. I was saying really that’s absolute nonsense. I think it’s a real conceit: the idea that you can contain anyone in an image, its absolute bollocks really.

TS Well, I might disagree with you on that. You can’t catch their entire being, their entity, but you’ve got to ask questions about what you think you present, as an actor. One thing, as a human being, you can never be sure of, is what we are actually like, how we come across to other people. An artist can capture something that the person doesn’t know they’ve got. Or if they do, it’s only abstract to them, ‘cause it’s a feeling. Whether that’s the soul or not is another matter. Somebody said about jetlag that you arrive in the country, and your soul arrives twenty-four hours later. So that’s why you feel so bad, ‘cause it’s somewhere in the ether and you have to go and get it from Heathrow.

SPW I just feel very cautious about that whole idea because… someone had been painted and it was suggested that the artist had caught this person’s soul, but the sitter later suggested that actually he’d had a really bad case of constipation while he’d been sitting for the picture. You know, that look of profound introspective melancholy he was wearing was really just…

TS He was backed up for a few days. (they laugh)

SPW He had a few trapped air bubbles up there.

TS When people who had never seen cameras had their pictures taken… and I think some people still are quite suspicious, because you’re taking something…

SPW …taking their soul away.

TS Well it is a bit of a cliché… [in an ethnic accent]: “you’re taking my soul”. But if you’re a good artist I think you do. Brenda Blethyn, who you painted, said she thinks the portrait you did of her was absolutely accurate, she wasn’t feeling very well. She was trying hard to be interesting. She wore too much make-up, and you caught it all. (They laugh) actors make a bit of an effort because they try and present something.

SPW Well exactly; that’s why I want to draw them.

TS But what they’re presenting, what you’re doing really well from what I’ve seen is you’re getting in, beyond the presentation. Also it’s a confessional thing, which is quite important between artist and sitter.

SPW Definitely. It’s a very specific kind of relationship, very unusual. It’s a very particular kind of intimacy.

TS Yes. Do you find that a lot of people tell you things that… it’s like a hairdresser…?

SPW It’s like a therapy session. People do tend to open up, if not in terms of actual revelations about their lives, at an emotional level.

TS Some of that is to do with you though. You’re very simpatico. You have an openness that people respond to.

SPW I think I probably ought to check that this has been recording …

TS I can’t remember all that.

SPW It should be working. I’ve got some questions here: erm, what is an actor?

TS Er, an actor is a person who has a desire and an ability to portray characters in plays and films and if they’re good, they make them seem real and people are entertained by them. An actor at his best can portray a character’s inner self. I’ve always thought that your job as an actor is to serve the character you’re playing. Some actors use the character to serve themselves, some actors play themselves, which is harder than it seems. So an actor basically is a poof who goes on stage, shows off and if he’s any good people are entertained by him and learn something about the human condition. [they laugh] I use the term poof as a generic term for someone who’s jumping around and showing off.

SPW …with a baggy shirt?

TS Well if you’re playing Hamlet, but, well that’s a facetious and ridiculous, but somehow true image. But if you’re a serious actor you feel compelled to do it. If I haven’t done it for a long time I feel odd.

SPW So you wake up in the morning and there’s a sense that you want to…

TS I leap out of bed, and jump on top of the wardrobe…

SPW …you want to be someone else?

TS …and I do all the long speeches from Tamburlaine the great, to the dog. [they laugh] I feel the need to express myself through my work. But it’s a collaborative art and so it’s difficult to do it on your own. If you’re acting really well people forget about that and they just watch the character, but that doesn’t win awards. It’s the actors who look like they are acting that win the awards. That’s why people who play cripples and weirdoes get…

SPW…because you can see them performing?

TS Yeah, and people go: “oh that’s marvellous, look at that limp. That lisp is superb” because most good acting isn’t noticeable.

SPW You mentioned the idea of self-expression. You said you feel a need to express yourself?

TS It’s not myself. I need a way to express a sense of creativity in myself. I need to feel that I’m creating something. When I was sixteen I had a big dilemma in my life; I was split between wanting to join the army and going to Art College and then in the middle of that confusion I was asked to do the school play and the two things came together somehow: the need to wear a costume and the need to express myself. Acting is the art of depiction; in depicting what is written, your job as an actor is to portray what the writer is saying. It’s your job to create something within that character that is multi-faceted, unless its an expressionistic piece, your job is to make that a completely believable human being, and for it to sit perfectly within the structure of what has been written. Your essence bends to fit the essence of the character you’re portraying.

SPW Is there such a thing as self, like a containable, or identifiable, essential Timothy?

TS Ooh, I don’t know. It’s a very difficult question, isn’t it? It’s almost impossible to answer, because… Being true to yourself and self, may be two different things. I would say that on the whole I probably do know myself quite well, and know when I’ve been wrong or unjust; I also know when I’ve got on my own nerves, so I do suffer more from being myself.

SPW When you talk about chastising yourself for behaving a certain way in certain situations, does that suggest that the idea of self is attached to a set of values which you develop, a set of expectations of how you will behave in any set of given circumstances?

TS I think so and also I feel I have an obligation to be mildly entertaining, I feel a little bit uncomfortable if I don’t make people laugh! I also have a great sense of the ridiculous. I always find myself trying to get to the centre of things that are borderline tragic and amusing, and I sometimes feel I have crossed the line because I take it a bit too far; it becomes bad taste. If I felt I’d offended anybody I would be mortified. The point of living is to become more and more like yourself which is a simplistic truism, but… so, I think self is something that you should constantly climb towards, but I don’t think you’ll ever know what you’re really like.

SPW No.

TS Buddhism is, er, the quest of forgetting yourself and thinking of others, isn’t it? So, there’s a similarity. If you think that self is about eating all the chocolates you can and getting as much money as possible and fuck everybody else, maybe there’s honesty in that? I mean. The Fuck you self is a perfectly credible self…

SPW selfish…an extension of self, perhaps…

TS Well, some people would say selfishness is a pursuit of trying to find out what you like, not what others like.

SPW What do you make of Oscar Wilde’s notion that most people are other people?

TS Now, I wonder what he meant by that. Was he talking about the mask of… everyone wears a mask, or was he saying most people are other people because only he is him?

SPW You sit down one Sunday afternoon and you watch Eastenders and there’s a scene in which there’s a break-up or an argument, and the bloke is telling his girlfriend that she’s a bitch and he’s fed up with her and so on, and he’s doing it in a very particular way: His gestures and the tone of his voice are stylised in a way that’s particular to Eastenders. The following week you have a row with your girlfriend and you notice that you’re using the same mannerisms and gestures that you saw on Eastenders.

TS Well you do see people behaving how they think they should behave and that’s part of the human condition isn’t it? All your influences come from other places. On daytime television you often hear a lot of people talking in that confession psycho-babble way without any understanding of what they are saying.

SPW Pseudo-Freudian…

TS Pseudo-studio! Pseudo-daytime-studio-talkio [they laugh]. But on the whole that’s how they present themselves. So what Wilde is saying is that people behave in a way they feel they’re supposed to behave instead of the way that they feel, but that’s just what society is. We are conditioned to speak in a certain way, to be polite and considerate to others. I think maybe what he’s also saying is what Sartre said, which is that ‘hell is other people.’

SPW Yeah, very true.

TS Because if I go out with a crowd of people I don’t know very well, I invariably don’t enjoy it, because I feel obliged to work hard to make them know that I’m alright…

SPW You want approval…

TS I want, um, approval. Yeah, as a human being…

SPW You want to be liked…

TS Yes! Yeah…

SPW We all want to be liked, so we adapt ourselves in order to accommodate other people…

TS Yes we do, but I do think there are people who are genuinely more inclined to be kind than others and that’s not the fault of either the kind person or the not so kind person, that’s a mixture of the way they are and their conditioning. You know, some of the worst murderers in the history of our country have been little men in car coats, who everybody thought was a nice bloke…

SPW Well, look at Harold Shipman.

TS Shipman, the guy who killed all the children in Dunblane, Christie, Yorkshire ripper. They’re people you sit next to on the train, who get their clothes from Matalan, I mean they don’t wear hoods and walk around with stilettos– knives, I mean, not the shoes. So, I think, in a sense, like a lot of Oscar Wilde’s sayings, they are designed to make you think, and they are…

SPW Provocative…

TS Provocative…

SPW Paradoxes.

TS Yeah, provocative paradoxical.

SPW What about: ‘being natural is only a pose and the most irritating one I know’?

TS [laughs] Well, there you go, we covered that…But the trouble is, nowadays young people are bombarded from day to day, by imagery that makes them feel inadequate if they don’t get what people are telling them they should have…

SPW Eating disorders are often caused by advertising. Most advertising works on the strategy of telling you what’s missing in your life and how you are inadequate: you’re not attractive, you’re too old, and you’re too fat, you’re this or that…

TS You smell…

SPW Yeah, you stink – but ‘we’ve got the answer, our products’…

TS ‘This will help’… I remember about twenty years ago I was doing a Mike Leigh play in which my character was a rat-catcher. What you always do with Mike, when you choose your character, is you go and research. My character had gone to borstal when he was young; so I was sent to a borstal in Dover, I was shown around by an avuncular warder, and I was taken into where the boys lived. I went in to one of their rooms and I expected to see posters on the walls maybe of footballers, girls with tits and all that, but this kid, on his wall, every single thing was either a picture of a Cartier watch, a Rolex, all of this stuff that he’d seen in magazines that he wanted, there wasn’t a pair of tits to be seen! I was amazed at that. This guy had been obsessed with things like that all his life, was obsessed with rich people and what they had. Anyway, we digressed…

SPW That’s alright.

TS …quite considerably, but probably all answers the same thing.

SPW When you’re acting are you Timothy or have you, in a sense, become your character?

TS I always try and feel like the character, I always try and become the character. If I don’t feel like I’m playing the character, as opposed to me, I feel like I’m cheating.

SPW So, you’re thinking as the character?

TS Well, it’s more complicated than that, it’s trying to feel like the character; the difference between impersonation and a performance is you know how you think the character will be, feel, talk and walk, and you get into character when you’re doing it. You don’t want anybody to see the gap between you and the character. So you’re job is to inhabit, that’s the word! Have you seen Monster?

SPW No.

TS Well, everyone was amazed because she’s a pretty girl playing an ugly murderer, but that was a classic example of somebody connecting completely with a character that wasn’t her; and actually she [the murderer] was alive when they made the film. The actress had met the person. John Hurt was the same when he played Quentin Crisp. Really good acting is somebody absolutely in the centre of the character.

SPW So, is it a process of empathy that’s taken to an absolute limit? in a sense, you’re empathising with that character to the degree that you begin to inhabit their mind-set?

TS Well, yeah, the secret is in the text, the rest is in your imagination, left to you to work out. The writer has gone through the whole process of putting that person on the page, and if it’s a good script, the sub-text is in there, but if it isn’t, your job is to think about that sub-text and what it might have done to that character, you then carry it like an iceberg. You don’t have to ever show it, ‘cause people who are demonstrably showing their research are the ones who have ‘give me an Oscar’ written on a badge – unless a person is like that; some people are incredibly preoccupied with showing you what they feel. There was a great example of acting last year. In the film: Being Julia, Annette Benning played an actress who was going through a terrible emotional thing. What she did brilliantly, was showing an actress who dealt with how she was feeling, in a theatrical way but, all the same, she still felt it. It was a brilliant performance.

SPW Well, that’s the idea of melodrama, isn’t it, in a sense? Isn’t that a kind of caricature of what is actually felt?

TS Well, melodrama is demonstrating without room for misinterpretation, that something good or bad is going on. Annette Benning was doing the complete opposite to that, which was showing someone who by nature is theatrical, dealing with a terrible emotional problem, who still couldn’t deal with it in any other way than being theatrical. And yet she was completely believable, whereas melodrama isn’t believable at all to a modern audience, unless it’s all heightened, then you get used to the style, something like Baz Lurmann’s… that musical he did …

SPW Moulin Rouge.

TS Yeah, I actually found that quite moving, although it was deeply heightened and expressionistic.

SPW surely, the whole point of any kind of melodrama like that, is that there’s a kind of truth contained in it…

TS Yes, you buy into the style, but it’s gotta be consistent…

SPW You buy into the language.

TS That thing of being heightened, theatrical and believable is part of the actor’s job as well, to sustain something consistently and to be in contact with the character; to be able to pay homage to the style, that’s your job as an actor. In this last Harry Potter film, there’s a point where a man loses his son and… you couldn’t really claim it was Stanislavskian – but, this moment is deeply moving because the whole film is made on such a heightened and brilliant level that it works …

SPW Within that language.

TS Yes, I think you can draw parallels with art : Guernica, for instance, a lot of people hadn’t had the time or the ability to divine what it’s about, might think it’s a load of old weird things, but if you look at it carefully, you see how moving it is.

SPW But you have to be party to the language, really, don’t you?

TS I think you do, well, you have to be educated, but I suppose that acting is a more direct way to engage with an audience. It’s more of an accessible way to make people understand an artistic notion; some people would accuse it of being a cheap way. It’s like music. Noel Coward said: ‘there’s nothing more potent than cheap music’ – which is true; you’ll be touched, really really touched by a terrible song, sometimes.

SPW All those terrible, schmaltzy, Hollywood movie soundtracks that make you feel as though your emotions are being manipulated by someone.

TS Is there any of that in figurative painting? do you use devices to make something more what you want to project into the character?… not dishonest ones, but:‘ I want someone to see this aspect of the character, which I can see but they might not, so therefore I will just… big it up a bit!

SPW There is something I’ll recognise sometimes, and it’ll be there for a moment, it’ll be just something in the fraction of the eyebrow or the relation of the iris to the eyelid, but as you’ll know, as an actor, these small things can convey so much. I look for those things, or I’ll just see them, and I’ll think ‘I’ve got to get that down; I’ve got to get that expression down, because that says something to me.’

TS Well, that’s the same in acting. When a character breaks down or shows vulnerability, if I feel a tingle of real feeling that he’s feeling, I know that the audience will feel that too; and sometimes I can do that in characters who don’t deserve it. And that’s one of my… if I may be so bold, my specialities, to make pariahs and gruesome characters sympathetic, and I like doing that because I think they deserve to be. I’m contradicting myself a little bit, because I said you just serve the character, but by serving a cruel character with a scintilla of some kind of vulnerability, you make him more understandable, he’s not just a pig then.

SPW Well, exactly, otherwise you’re just playing a stage villain; you’re playing an archetype, and surely the point is that everybody, in a sense, believes they’re doing the right thing, by their own moral standards…

TS Do you ever get touched by somebody you’re drawing?

SPW Only on a good day. [they laugh].

TS But, I mean: affected. Can you see something in somebody and be moved by it.

SPW Definitely, completely. I find it very difficult to paint my mother for that reason, because, in a sense, I find I almost see too much.

TS Your connection with her is something that…

SPW It becomes painful… when you really examine someone, as you do if you’re painting them, that can reveal a great deal of the sitter’s vulnerability, both physical and emotional, and if it’s someone that you’re as close to as your own mother, that can be very difficult to deal with…

TS Of course, yes, well, I think that’s what makes acting not just an exercise in showing off in a mildly entertaining fashion. When I read a part I’ll look through and make connections and it’ll say “he laughs with triumph” and you think ‘now is that triumph? Or is there a mixture of fear under the triumph’; why is this person like that, how can I show the audience that this character is the way he is because he’s in pain. So you’re trying to get into the character’s soul with a probe, and then trying to connect that with your own soul. Then you present it to the audience.

SPW But when you inhabit that character, do you lose your sense of timothy-ness?

TS No, you can’t really, because you’re the vessel. When I play a character… recently I played Albert Pierpoint, who was Britain’s most prolific and celebrated and then derided public executioner…

When I read the script, it was extraordinary because the story is seen from his point of view, and it’s incredible what happens in the movie, because you hate what he’s doing but feel empathy for him. In his latter days Pierpoint had become a bit of a celebrity; he was on chat shows. I spent a lot of time watching him, and the interesting thing about him was that he was a very jolly man, on the face of it, a very honest man, and very respectful. Yet every now and again there was something in him, a spark. Looking at his photographs there’s something both messianic and ruthless about him, and yet sympathetic at the same time, really interesting the paradox of this man. He hanged 603 people, so when I played him I was very conscious of trying to capture that very paradoxical quality in him: always showing [adopts northern accent] ‘he’s like a normal man who’s prepared to do his duty and doesn’t like talking about things.’ And when I was doing it, I always felt that I was Albert, I always tried to speak a little bit like him and walk like him. Then when I saw the first rough cut screening of it, I thought ‘no, no… no, that’s me. That’s not Albert’, because when I was doing it, I felt I look liked Albert, I felt my face was Albert’s, and when I looked at the screen and it’s me I thought’ no, no, it’s wrong, that should be Albert’.

SPW Throughout what you just said, it sounded as though you do lose your sense of Timothy-ness when you’re acting.

TS You do, you can’t lose your sense of control over what you are doing, because your ability is in making that character… you’re working to make it, it doesn’t just come.

SPW But when you’re in the midst of that you’re not thinking about what’s for dinner that night?

TS Invariably not.

SPW So, do you draw on a vocabulary of emotions that you have stored up?

TS You have to; sometimes you have to think of bad things, upsetting things, if it won’t come.

SPW In order to try to understand how a character would feel in a certain situation.

TS Sometimes you just have to do it technically, because you might have to do it more than once, and I defy anybody to feel… when we did All or Nothing, the big scene where we both break down and tell the truth to each other, we shot that over two days, so to get that emotion each time, you had to do it technically, to match it with what you’ve done before. Of course, the director will draw from more than one take, to make a performance. Sometimes you remember how you did it when you felt it and you’ll play it, what it felt like.

SPW But without feeling…

TS Without feeling, and you’ll feel a little bit cheated, but if you know what you’re doing, I defy people to notice the difference, and sometimes when you connect with it, it doesn’t mean it’s necessarily coming across.

SPW Do actors hide behind their characters?

TS I don’t think they do. Some people are confused about who they are, feel more comfortable acting than when they are walking around in the street. It gives definition to what they feel, so I think that some do actually But, on the whole, they don’t… I remember having to go and do a performance of Bottom in A Midsummer Night’s Dream at the National after I’d given a eulogy for my father in law’s funeral and play this jolly… and also when I was told I was ill, I was playing a jolly plumber in a commercial so when I was doing it I was thinking ‘Jesus Christ, I’ve just been told that I might die!’ But I felt I had a contractual obligation to do the character. No, I don’t think actors do, it might be a relief to some but, on the whole, it’s a job that you do. I suppose it could be cathartic in some way, but acting is also exercising absolute concentration, which might help you forget something for two seconds. It’s a bit like going to sleep knowing that you’re going to have to have a terrible operation in the morning and when you wake up you think ‘ahh…’ then you go: ‘oh no, I’ve gotta have me legs off!’ [both laugh].

SPW What do you make of the idea that ‘actors simply do, only in a professional capacity, what the rest of us do in our daily lives, that is: play out roles. Do you think we are all actors really?

TS No, I don’t think so. I’m not a very good liar. If somebody told me to tell a lie, I wouldn’t be able to act it, I’d have to really concentrate and learn the character, I couldn’t just do it naturally. Actors are people who are employed to depict the way others behave in a controlled environment and then it is used as a form of entertainment. I think people are going abut their everyday lives just trying to get through the day without being shouted at, run over or losing their job [they laugh].

SPW Well, that kind of covers the next question, which is ‘do you think that human existence is an extended theatrical performance?’

TS No, I don’t think it is. It would be easy to relate to that if I wasn’t a professional actor. I know what the difference is, ‘cause I have to do it…

SPW You know when you’re performing and when you’re not.

TS Absolutely. And I know the difference between the styles of performance and what they’re aiming to achieve. On the whole the human condition is aimless but it’s natural and even though there are elements of people hiding, people performing, it’s not controlled; people, on the whole, don’t wake up in the morning and go [puts on affected accent] ‘if I behave like this everybody might think I’m marvellous’, you know, they…’

SPW But you mentioned that you don’t really like spending a lot of time with people that you don’t know because you feel the need to perform…

TS No, it’s not performance; it’s making an effort to be entertaining and accepted. Having achieved a certain amount of fame, sometimes I want to let others know that I don’t think I’m ‘marvellous’, that I’m just a person, that it doesn’t make a difference that I’ve been on the television a lot and blah-de-blah, I mean, we’re all shy. Isn’t it funny, some shy people can seem rude? Sometimes you think ‘come on, make a fuckin’ effort, we’re all shitting ourselves, what gives you the right to sit and look shy and make everyone think that you don’t like them?’ Isn’t it funny? I feel a great desire to share with other people… a sense of the ridiculousness and the paradoxes…

SPW The absurdity of it all.

TS The absurdity of it all, and I just enjoy… high-flown nonsense; I remember one bloke, I met this bloke in a bar in a hotel in Manchester, we were chatting and I asked ‘im what he did and he said he was a water-filter installer, and I said ‘ah, tell me more about that’ and he was talking ‘bout five minutes about it and he stopped and said [adopts Lancashire accent] ‘are you taking fuckin’ piss’, I said ‘what?’, he said ‘ you can’t be interested in this, this is fucking boring’, I said ‘no, I am genuinely interested, actually.’ He just couldn’t understand that I would be interested, but…

Transcribed by Gavin Wright, January 2006.