Love and Death

This project formed Stuart's third exhibition at The Riflemaker Gallery in 2013.

LOVE AND DEATH

by Rosie Millard

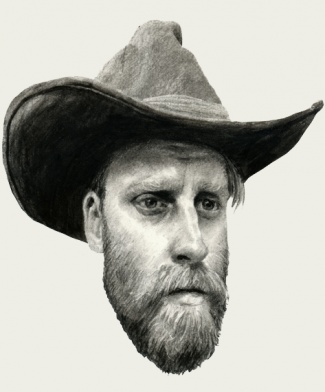

In a way, it’s just as well that Stuart Pearson Wright did all those portraits of famous people when he did. Winning the BP Portrait Award in 2001, aged just 26, with his extraordinary multiple portrait of past and present Presidents of the British Academy, he was then put firmly on the landscape, and as such, commissioned to paint luminaries such as John Hurt, the Duke of Edinburgh, and J.K. Rowling. A few years later, he made a surreal short film with the film star Keira Knightly, whom he apparently fascinated, by turning up to watch a play wearing plus fours. She was intrigued and agreed to be filmed wandering around the maze at Longleat dressed as an Elizabethan lady, searching for Wright (who was in a ruff).

Having triumphed with the not inconsiderable pressures of dealing with hyper celebrity – without for an instance lurching into cliche or dropping his own exacting standards, Wright then moved firmly into his own world of friends, family and imagination – yet with the earlier stardust still apparent. It is as if he released himself into another world, but bringing the red carpet of fame and theatricality with him.

His work was playful, funny, deliciously irreverent and iconoclastic. Now, however, it has changed again. Wright’s world may still have a glossy sheen to it, but it is now a far more dark, intense, almost Gothic one. In some ways, it is easy to understand why.

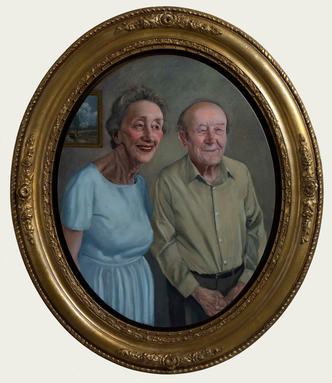

Wright, who is still under 40, is now married to his muse, the beautiful Polly. They have a cherished and adored son, Wulfred, 2. The heady eroticism of Wright’s early work, much of which featured portraits of Polly, has been tempered by the burning uncompromised love which comes with the sober realities of parenthood. The oval portrait ‘Bubbletime’, of Wulfred stepping nakedly and joyously through the grass is both a contemporary nudge to Lord Leighton’s iconic Bubbles, and a poignant acknowledgement of the fleeting beauty of youth - vanishing almost as fast as a popping bubble. It is so bewitching and heartfelt that it is almost painful to stand in front of it.

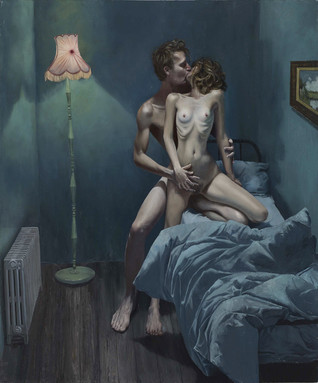

Love & Death

As titles of an exhibition go, it doesn’t really come bigger than this, and yet Wright has dived into the field with characteristically forthright brio. The triptych which carries the weight of the subject was devised by him in his studio with cinematic care. As a boy he would imagine his life as a film, building tiny sets inspired by Star Wars, and writing screenplays. Here, he has imagined the passage of human life as three theatrical set pieces; Conception, Birth and Death.

Each painting was devised in a special ‘stage’ built by Wright in his studio, an industrial space in East London. A steeply raked floor and theatrical lighting heightened the sense of displacement. He tells me he desired an almost Brechtian take on our mortal fundamentals. These are elements of our existence that we all well know, but in a sense take for granted until they are brought before us like this with such strange demeanour. Using life models and actors, (and a very realistic ‘baby’), Wright forces us to engage with the throbbing heart of mortality. This is thrilling, moving, serious work from an artist at the height of his powers. There is still a playful smile there, the joy of seeing the world in heightened colours, the delight in the figure, but what is now apparent, more than ever before, is the very profound core of his work.

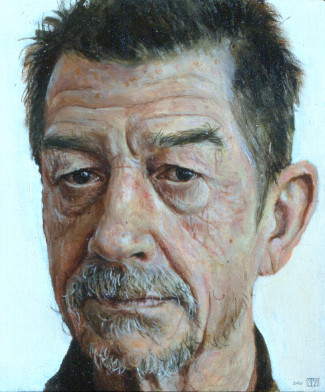

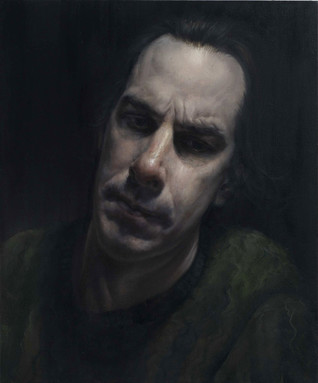

A portrait of his friend Phil Hale is entitled Weltschmertz – or World Pain. This is the work of a mature artist, one who is still enchanted with the bubbles of a child, but who can also measure the weight of the world alongside them. “Phil always looked as if he has the troubles of the world on his shoulders. That was what I wanted to convey,” says Wright. “As a figurative painter, I was growing tired of being ironic. I was tired of traversing the minefield of sentimentality. I wanted to make a show more from the heart,” says the new father. “And I decided it would be about relationships, primarily between parents and children.” This, from a man who never knew who his father was (Wright was brought up solely by his mother Penelope, a painter herself).

Gone is the previous playful ‘chocolate box’ approach, where Alpine views, trashy films, Snow White and country music were bound up with an off-kilter, surreal flourish. In this new show, Wright drops the jokes and tells it like it is. And yet it is not in any way ponderous. There is still an electrifiying theatricality to his vision; a sense of surreal distortion, an hyper reality. His portrait of his parents in law Margaret and Roy is one such picture (and look out for the art history reference in the corner).

It is telling that the inspiration for this show came from the Wallace Collection, where country maidens cavort alongside harlequins in Watteau’s fetes galants, and landscapes are suffused with a strange glowing presence, as if the volume has been turned up by several degrees.

There is innovation; the two paintings entitled The Ocean Doesn’t Want Me Today have been painted over layers of transparent resin, giving a strange, shimmering effect as if they are being viewed through water.

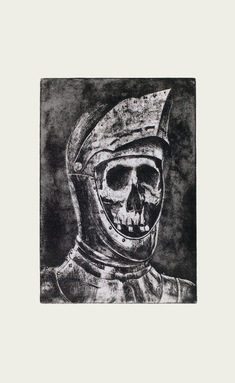

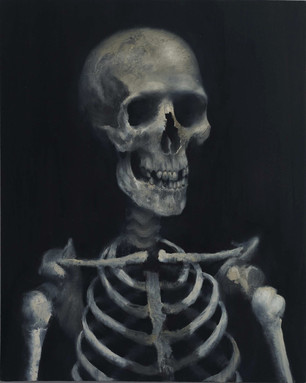

The skull is a formidable motif throughout, both in sculpture and painting. It relates not only to our own sensibility of mortality but also a classic Gothic story, the Spectre of Brave Alonso. Of course, story is crucial within this shimmering, intriguing show, Wright’s third at Riflemaker. There are familiar narratives – Alas Poor Yorick, where Wright casts himself as Hamlet is one – and unfamiliar, invented ones to plunge into.

Who knows what the original narrative may have been behind the extraordinary Tonnara di Scopello (the title refers to a Sicilian site used for tuna fishing), where a naked woman sits by the sea on a rock, reflecting thoughfully on a bloody, severed penis positioned on a coffee table before her, a whippet at her knees.

“I thought the model ought to be looking at something,” he says, cryptically. “And I was fed up with painting skulls. So if it wasn’t going to be a skull, it had to be a willy. And once there was a willy in place, there had to be a whippet,” he says, smiling. Quite. Whatever was going on in Wright’s brain, you can be assured that the viewer will invent a narrative of his or her own.

“A long time ago, a creative writing group used a painting of mine as an inspiration for a writing exercise,” he tells me. “I was shown what they had written. It was fascinating to see how people had understood my paintings.”

There is something about Wright’s viewpoint – the heightened lighting, the cool palette, the theatricality, and the quirky proportions – which releases the viewer from straightforward comprehension of the subject matter into a thrilling narrative of his or her own. This is why I think it was so crucial that he painted overly familiar – even slightly tired – subjects, at the start of his career. To deliver the jowly face of the Duke of Edinburgh, the creases of John Hurt or the thin cleverness of JK Rowling in a startlingly innovative way, as he did, is an achievement indeed.

Wright’s world is so extraordinary that even the most bathetic of images – that of parents holding a child by each hand, perhaps to swing it aloft – as in the painting Haggerston Park – is given an arresting sense of ‘difference’ which makes it seem charged, unique and so very different from (say) a cliched photocall with Ed Miliband and family on Brighton Pier.

In this, Wright represents a very British school of art; that of the singular painter. It is a school of outsiders, championed by the formidable likes of Stanley Spencer, or Edward Burra. Alumni of the Slade he may be, but there is nothing about Wright which indicates he is part of a group. His paintings are highly individual, and utterly distinctive in their mannered strangeness. Their humour, life and sense of theatrical story embrace the viewer, yet their coolly distorted perfection insist on a distance between viewer and canvas. It is this constant two-step which makes them so remarkable, engaging and unforgettable.

September 2013

STUART PEARSON WRIGHT IN CONVERSATION

with Jock McFadyen

JM I used to teach one day a week at the Slade and met you there. When was that?

SPW 1925 or thereabouts…

JM 15 years ago?

SPW A long time ago. I was in shorts. And you had all your hair.

JM Then you won the BP portrait award in 2001.

SPW You were one of the judges. I had given you that envelope with all that money in it just prior to the prize.

JM Right. What struck me about you at the Slade was, that you were a gifted draftsman. Some people can draw and some can’t. You acknowledge that don’t you?

SPW Yes I think so.

JM You’re the kind of person who would have been gifted enough to have been accepted at the Royal Academy or the Slade In the 1930’s. Maybe you’d have had to be more posh, but lots of today’s contemporary artists simply wouldn’t have been accepted because they can’t draw. When I met you I thought: “Oh dear, here’s someone who can draw. How the hell is he going to get on in the art world?” (Laughter) How is he going to be taught anything? The best thing he can do is to start making videos. Either that or disappear into the life room for four years and emerge as a nonentity. It’s basically true isn’t it?

SPW It is. Being able to draw well can be a handicap. Everything you make is determined by your draughtsmanship. Painters like Justin Mortimer and Phil Hale, both incredibly gifted draftsmen, seem to spend most of their time battling against their own skill…. Neither of them can make an ugly mark.

JM There is a distinction which should be made between painting and drawing. A lot of people can draw well but can’t paint. You weren’t like that. When I first saw your work in one the seminars, you were trying to make a London bus and you added some metal filings to make the paint go rusty. I realised this bloke can paint as well as draw, he’s excited by paint. It turns him on. He can make it do things, and he wants to explore it. He’s really fucked. (laughter) What is he going to do? Humphrey Ocean also won the BP Portrait Award but in 1982. In a way it’s like saying “you’ve won this prize. That’s the good news! but your career is over.” (laughter) I watched Humphrey pedalling away from the perception of himself as a portrait painter.

SPW I’ve been pedalling in a similar direction.

JM I still think portraits are incredibly important. Conceptual artists like Cindy Sherman or Gillian Wearing who don’t even paint, make portraits. So it’s funny that a natural portrait painter has to, in order to be successful in the art world, not do portraits. That is part of a trajectory that you’re on isn’t it?

SPW I’ve tried to establish the same fact as Humphrey, that I’m an artist and not just a portrait painter. I find that description limiting. I also work in film, sculpture and printmaking, and I paint things which aren’t people as well. Crucially for me, even when I do paint a figure I don’t think I’m necessarily making a portrait per se. A portrait serves a specific function. It’s about the identity of the subject. Most of my figure paintings are theatrical constructs and not about the person who has posed for them at all.

JM In the pictures in this exhibition there are protagonists and narratives. The difference between you and me is that I invent people. You need someone in front of you to paint like Lucian Freud might? Although I’ve seen you working from photographs.

SPW Yes I do sometimes work from photos now. I never used to. I would like to be in a position where I can work from imagination. I’m edging slowly towards that but it’s a leap for me to make. Although I certainly could paint a head without any reference, particularly my own head.

JM But if you’re going to present anything like character you do need references, some form of observation: photographs, drawings or a mirror even. I know that you’re interested in a variety of media but I think essentially you’re a painter. it’s the dilemma of a painter that you want to understand the unfolding story of painting. I’m maybe more of a landscape painter in latter years and I’m interested in the future of landscape painting. What can you do with landscape now which you couldn’t before? Art’s in a different place and so is the landscape. With figurative painting, do you feel that the options are closed off because there are ironic painters like John Currin or dreamy painters like Peter Doig or straightforward portrait painters like the ones at the Royal Society of Portrait Painters?

SPW It’s a minefield really. Trying to paint figuratively is like walking through a minefield. It’s very difficult.

JM And is part of your job about defining, positioning yourself?

SPW I think you’re always having to think about where your work is going to sit within that minefield. Is it becoming sentimental? Are you being too straight with something? There’s always a compulsion to give something an ironic twist. In my last Riflemaker exhibition I felt I had made some of the work too ironic and it became cynical. I wanted to avoid cynicism in this body of work, to approach themes like love, loss and mortality without having to resort to irony or flippancy and something that has run through the work of mine which I like the least: The ‘one- liner’.

JM It’s difficult. You have to position yourself against the backdrop of contemporary art which is in a terrible place at the moment because of it’s huge success. Art’s more popular than it’s ever been, but to find real art you have to fucking dig down. Irony has been done to death. The thing that irritates me about contemporary art is that it has to demonstrate how clever it is.

SPW Yes I find that really tedious.

JM Art should be above that, more spiritual. It’s complicated now to make figurative paintings. You have to describe where you are coming from. You can’t burden the painting with that kind of explanation or the painting just becomes about that explanation. And that’s shit isn’t it? It’s making painting loaded with it’s own justification. So it becomes a conceptual painting about itself.

SPW Well that’s my main problem with contemporary art, the way it’s explained and described. The language of art theory is so jargonistic and pretentious: just a means of conveying to the listener the intellectual prowess of the author. What would Orwell have made of it?

JM Do you think the same thing is true of the novel or the feature film? Or do you think they’re in a freer position?

SPW I think they are freer because they’re moving and time based, meaning is often implicit or easier to extrapolate somehow. But I think with art there is a culture of…

JM Convolution…

SPW Well there’s a need to always over-describe something. For me it’s like in the middle of sex, having some irritating biologist standing next to the bed and describing the process of what’s happening in biological terms.

JM I see. That’s a very good way of putting it.

SPW And you see, it spoils the moment.

JM Well I don’t have a psychologist in my bedroom but yes it must.

SPW I can't think of anything worse than being told by someone else what something is or means: that immediately paralyses your own response.

JM It seems to me that you’ve always been the man that’s hugely energetic, and you’re still young.

SPW …ish.

JM You were like a greyhound out of the traps.

SPW Waning now that I approach my forties.

JM Remember you’re talking to an old bloke. You accomplished a lot quickly. You kicked off winning perhaps the most reactionary art prize there is. Do you think that you’ve been powering away from your perception as a portrait painter, and now you’ve gone so far that way you’re coming back again? Have I got that wrong?

SPW To an extent, but the power of the thrust of my movement forward has always come from trying to avoid poverty: coming from a humble background and knowing that I didn’t have a plan B. I have always known that I was otherwise unemployable. That has given rise to a thrust forward.

JM But you could have stuck with society portraiture and made a good living from that.

SPW That’s true, if it was just about financial success it would have made sense to have just stuck with commissioned portraits.

JM It’s not the powering, it’s the direction.

SPW I have been motivated to inform people that I am an artist rather than a portrait painter, for what that’s worth.

JM Do you think you’ve been to the wildest shores of irony and now you are bouncing back towards narrative and storytelling? With narrative, you don’t really have to be that ironic. It could be like a Mike Leigh movie. There’s something old, ordinary and humble about Mike Leigh’s characters. There’s no real sneering irony, though there is humour.

SPW It’s funny you mention Mike Leigh because at least until I painted his portrait he was a fan of mine and an advocate of my work.

JM You’re interested in film.

SPW Films are an important influence on my work and I’m interested in performers, in the idea of performance: actors. I’m interested in the process of acting, of pretending.

JM What about narrative though? Or are you more wanting to talk about artifice?

SPW Artifice is an important theme in my work: the idea of someone pretending to be something, even if it’s just pretending to be themselves in the context of posing for their portrait.

JM So everything’s always artificial?

SPW I believe so. As Wilde said: “Being natural is only a pose”. I often leave little clues in my pictures to that effect. In this Hamlet painting ‘Alas poor Yorick’ the skull has clearly not just been dug up. It’s got a little brass hook on it. It’s from an anatomy room. I like to reward the people who look very closely. They’ll see that it’s a prop, exposing the machinations of the performance, as Brecht did. It’s not a real scene, or even a play with a real actor. It’s me, pretending to be an actor, playing hamlet. There are several stages of removal. And yet the painting is still about mortality and loss though seen through several filters.

JM Where does a classical painter go in today’s art world, who deserves to be taken seriously, and wants to take painting forward? These paintings are full of narrative and over acted. Whereas the portrait of Phil Hale (Weltschmerz) is something else completely. You can contemplate it in terms of the pure humanity of it as a portrait. Is there a chronology in these paintings?

SPW There is a chronology between these three pictures. They are conceived as a triptych.

JM So that’s the birth and the death…

SPW And the conception.

JM Oh the fucking one. That’s the best bit isn’t it?

SPW That’s half finished.

JM Ha. That’s no good.

SPW The conception is half conceived.

JM I see, so that’s a triptych. It’s not that the whole show is one story?

SPW No. And in fact I was concerned initially whether or not the work would hang together well.

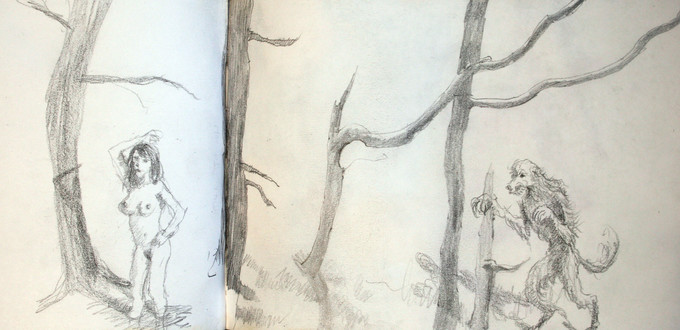

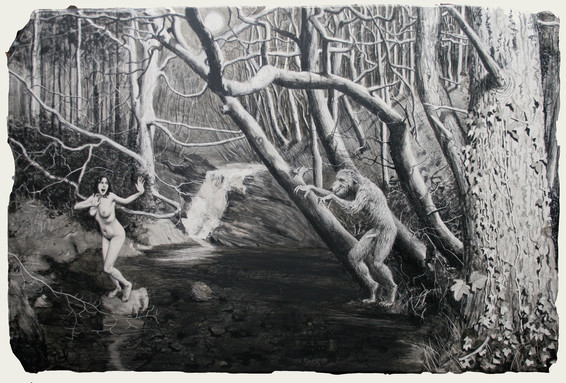

JM These three skeletons are funny. They’re much looser than your usual work.

SPW Yes. That one is called ‘The Spectre of Brave Alonzo’. The sculpture that I’m making is of the same subject. The reference is a short story within the early Gothic novel: ‘The Monk’ by Matthew Lewis. It’s a funny little story about the inconstancy of love: Alonzo the knight goes off to fight in Palestine. His fiancée swears to remain true to him even if he dies. She adds: “If e'er I by lust or by wealth led aside, Forget my Alonzo the Brave, God grant, that to punish my falsehood and pride Your Ghost, at the Marriage may sit by my side”. And of course that it’s exactly what happens, he dies, and then he turns up at her wedding, clad in armour with a skeletal face: “The worms, They crept in, and the worms, They crept out, And sported his eyes and his temples about”. He takes her back to hell. I’m not sure why I found the image of a knight with a skeletal face so compelling but I made four pieces of work based on the story: a painting, sculpture, drawing and an etching. Does the body of work hold together well as an exhibition?

JM Yes, but hanging is going to be important because you’ve got to dispel the idea that there’s a running thread of narrative. But there is a vague theme. The idea that you can paint stories is something new I think.

SPW New within my work?

JM Yes, new in the unfolding story of SPW’s paintings. Because in the cowboy paintings and the others that I’ve seen recently: Tom Jones with his glittering diamond watch: they were jocular and frivolous.

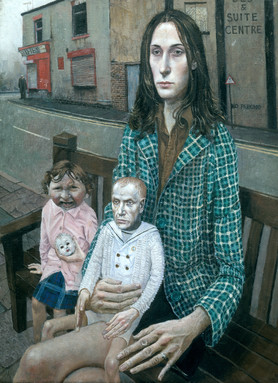

SPW Yes, it’s certainly a move away from that. But the narrative element which you describe as being new, feels to me like a return to earlier work. There’s a painting I did at the Slade called ‘Middlesbrough’. which could hang very well with this exhibition.

JM I was going to talk about that painting. It was very accomplished and it had lots of elements which I sympathise with. It was like those post war movies: ‘Room at the Top’: grainy British realism. Look here we are in this fucking shit town, with this single mother who is on the dole, with this baby who looks like an old man on a wet Wednesday. It was very English. English failure: they wouldn’t understand that in America, they just would not get that painting. They get John Currin, with his paintings of women with upturned tits, because it has been spelt out for them. And that’s what’s so great about Damien Hirst’s piece: ‘Let’s eat outdoors today’. there’s white plastic garden furniture with a plate on it and a slab of beef, flies everywhere. You can imagine Timothy Spall sitting in there in a shellsuit. You could take that anywhere in the world and that’s English art. It doesn’t have any debt to Warhol, Rauschenberg, Pollock or Picasso.

SPW But you could relate it to Mike Leigh.

JM You can relate it to Mike Leigh and Ken Loach, because it’s part of our culture.

SPW Do you think 'Middlesbrough' makes a similar sort of statement in a way, or is similarly English?

JM Yes. All these years I have been selling paintings, being pissed off because I haven’t sold them for enough. I now realise, if you don’t sell work you are doing something right. When I was at art school, people who sold a lot of work were regarded as being very commercial. There was a snobbery about it. Now that art has lost its critical backdrop: there’s no real intelligence in contemporary art crtitism. It’s gone to the market for it’s validation. The artists who everyone admires are the ones who sell the most.

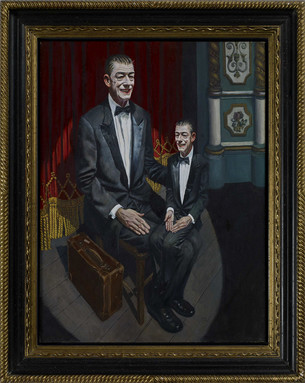

SPW In relation to the return to narrative that we talked about, another picture of mine which was similar to ‘Middlesbrough’ was ‘the Ventriloquist’. Did you ever see that one with John Hurt sitting on his own lap?

JM Yes I saw that one when you were painting it .

SPW With the same sort of stiff, puppet-like hands that the figures in ‘Middlesbrough’ have. This painting here of a mother and daughter called ‘Orlagh and Keira’, reminds me very much of ‘Middlesbrough’ and also ‘the Ventriloquist’.

JM It’s very similar to both of them in fact. You’ve been on some kind of journey or a little holiday to ‘ironyville’, and then back to some kind of realism. When I left art school, the thing was to try and make myself visible. A lot of my work was very humorous, witty and self referential. I was very successful with that work and then began to wonder whether I could sustain that kind of painting for the rest of my life. I realised that I needed to start making work that I’d still be making when I died. I couldn’t carry on making art jokes for the rest of my life.

SPW Well I think I came to a similar position . During my last exhibition I realised I’d gone down a cul-de-sac. There was one painting called the ‘Olympian’.

JM The blonde chap with the large foreskin.

SPW That’s it. The canvas was anointed with ‘Old Spice’ aftershave. But I realised it was a one-liner. It appealed to my sense of humour but maybe not to anyone else’s. I felt, in reaction to that, I wanted to make something which was more sincere. That was the starting point for this show. But that threw up other landmines, like sentimentality.

JM Oh, I don’t care about sentimentality. I think that in literature, movies and paintings, I like things to be stripped down and to the point. But if you’re going to tell stories you need detail.

SPW I’m not sure you do. Think of Samuel Beckett’s ‘Waiting for Godot’, you’ve just got a dead tree and for the best part of the play just two blokes on stage. That’s the way that I want my painting to go, that’s where I’m trying to get to.

JM Well you’re not there yet.

SPW Not at all, but I’m working towards that. This conception, birth, death triptych is the first step. In order to paint those I built myself a stage set and filled it with people and props, then lit and photographed them. That’s the way forward: staging my paintings in a box like a theatre director. My realisation is however, that I don’t need so many props.

JM Less is more.

SPW Exactly. I want to be able to make a painting in the way that Beckett writes a play or a story, to strip away all the extraneous shit.

JM That’s going to be the next exhibition.

SPW This Hamlet picture is probably the most detailed painting I’ll ever make. I want to make sparse paintings that are more about paint than about the subject, in which there’s less going on.

JM So this exhibition is kind of a half-way house on the way to something.

SPW It is a transition. But one could argue that an artist is always in transition: evolving. When I’ve made those sparse paintings I’ll probably be aching to make paintings that are full of props again.

JM And yet success in the art world always goes to artists that never change anything about their work. Even Bacon didn’t really change very much. The work I’m doing at the moment wouldn’t be recognised by people who knew my early work.

SPW I think it redefines you. I think your current rude paintings are the most important thing you’ve done.

JM Well maybe. I’m enjoying them, because I get bored doing the same thing. I couldn’t be Sean Scully: Another day, another stripe. If you want to be successful you have to dumb right down. The further down you go intellectually, the more people, the more sales.

SPW Look at Vettriano.

JM That’s different. He’s making images. He sells to people who make black venetian blinds, who still think it’s 1987: people who go to wine bars where there’s chardonnay on the piano, where they think it’s sophisticated to have drinks with umbrella’s in them. He’s away with the fucking fairies. Reiteration: that’s what artists have to do now, because there’s so much art. “I’m the guy who does the naked cowboys!” That’s you. “I’m the guy who did the big empty landscapes remember me? And now I’m doing something different.” That’s no good. It’s a dealers nightmare. Look at Bridget Riley. She’s never changed.

SPW She’s been doing the same old thing for years.

JM But it’s boring to stay still isn’t it? Maybe your way of painting hasn’t changed much because there’s complexity in figurative painting. I think it’s not so much transition as a question of taking little journeys out. It seems the thread with all of the work is narrative. I suppose it’s only fair for the viewer to ask: “What’s going on here? Who’s that?” and so on…

SPW What do you think is going on? What do you think of the work? Do you think it’s any good?

JM Oh yes, I think it’s good. I don’t really care what you paint. My eye goes to some things more than others. It’s the paint and the figure. You can decide that you’re going to be a certain type of artist. Then there’s the other route of just muddling through and then getting to a point where you might be fifty years old and you say “I wonder what kind of artist I have turned out to have been?” And you turn round and you see where you’ve been and say “Oh I’m one of those artists, I didn’t really want to be one of those. Yet the evidence is undeniable.” I think that’s the right way to be, to muddle through. I think that artists who project, and then follow through are crap really.

SPW Do you not consider those kinds of artists courageous? To have an objective, and to have the willpower not to waver from a certain vision?

JM No I don’t think so.

SPW I mention that because I talked of trying to make my work sparser, and more about paint than subject but I always seem to fall short of that objective.

JM Well maybe it’s not in you to be like that. That’s the point.

SPW But does that make me spineless?

JM No it makes you intuitive and not able to bring yourself to do something that’s not in your nature. I’m on the side of intuition in art. I think that if it's not in your nature, even if you want to be a different kind of artist, you end up being what is in your nature. That means that you end up using the art as a divining rod, you’re following it, you don’t know where it’s taking you. And that’s the right way to be, otherwise it’s just fucking boring. You might as well get a job if it’s not going to be mysterious and frustrating, because you think you’re looking for one thing and you find another. Humphrey Ocean’s great gift is being able to draw with a brush, loaded with paint dripping off it without taking his hand off. That’s pretty fucking cool. Fast, quick, intuitive, nailing something that’s so true and right. Most of the people teaching in art schools can’t draw for toffee so there’s a resentment towards the people who are gifted. I remember a boy who came to the Slade, he could draw incredibly well. He was very young, from the provinces, middle class. I think he was a virgin. He went to church and things. He wasn’t like an art student but he could draw like an angel.

SPW Did they hang, draw and quarter him?

JM No. I was talking to Patrick George: “So what do you think of that boy?” He said: “Yes terrible, one doesn’t know what to do with him. He might have peeked already and he’s only eighteen.” You only have to look at the BP Awards. Half of them aren’t even artists and yet they can draw better than most famous contemporary artists.

SPW But just how interesting is it to get the ear or the nose right? A lot of those paintings are about anatomical correctness and little else.

JM I’m not making a quality judgement about the work in the show. What I’m talking about is the ordinariness of being gifted.

SPW And the limitations of technical competence.

JM The thing is, being gifted now is almost nothing to do with being an artist, in the way that we’re talking about it. We’re having to figure out a way of being visible in a contemporary art world, and yet to be true to ourselves as depictive painters. I like the problem of playing it straight. Edward Hopper painted mid west filling stations all the way through the fifties, while abstract expressionism was in its ascendancy. He’s painting nighthawks, or Early Sunday Morning, making exciting paintings. But he might as well have had a sign on his head saying ‘Provincial Boring Throwback’. Now of course, people think Hopper’s great and when you see Pollock now it looks like some quaint, old fashioned idea about modernity that went out of fashion about 1959.

SPW I’ve never had much time for Pollock I must admit.

JM That’s my point. When I was at art school Pollock was a god. Hopper was just an embarrassment. “You don’t like that shit do you?” That’s sentimental, as you put it. Now people read all sorts of things into Hopper. They see the bleakness: the lonely nude woman in the ominous hotel room without a lover. Then you look at movies, The Soprano’s: all those shots are stolen from Hopper.

SPW Well they’re very filmic aren’t they.

JM They’re filmic Yes. It’s a question of being true to yourself. People who were at art school in the seventies were the first wave of figurative artists to be taught in art school by abstract painters. It’s not quite the same for you because you were just taught by bad figurative painters.

SPW I just feel that I wasn’t taught at all, to be honest. I don’t remember anyone saying “what about using the brush like this?” I just had to figure those things out.

JM Me too. I wasn’t given technical advice. I only started painting on different coloured grounds about fifteen years ago, realising that everything is affected by the colour of ground you paint on. Nobody talks about the language of painting anymore. Lets move on. Fuck it. Narrative: that’s your touchstone at the moment is it not?

SPW With this exhibition certainly.

JM It’s a story, using painting as a documentary form. saying “I’m going to show you these people and tell you about them”.

SPW This picture I’m working on at the moment…

JM The shagging. The conception.

SPW I’m enjoying painting it. It’s something to do with the light and the colours. The turquoisey wall is reflecting light onto the right hand side of the woman’s ribcage so that on the underside of that breast there’s a weird greeney-blue light. And because the bloke’s shoulder is close to the lamp, there’s an orange light on that. You’ve got orange reacting against turquoise, reacting against malachite against pink. For me, these colour combinations are quite daring, I’ve not painted colours like that before.

JM Did they really fuck in front of you?

SPW No. But they were very fond of each other. They are a real couple. That was very essential. They are very much in love.

JM The thing is Stuart that you’re talking like a film director here.

SPW Well I think that the process that I’m using to make my paintings is analogous to film. It happens on a stage set with actors. I’m thinking about props and lighting, setting the whole thing up and then recording it.

JM The fact that art schools don’t even have life rooms anymore reflects the fact that there’s a fucking crisis in art education. When artists have to jump through hoops, in order to justify the kind of artist they are, that’s terrible.

SPW Knowing people who’ve just come through the art school experience, they have to spend a great deal of their time writing about what they’re doing and why they’re doing it. I always give them terrible advice…

JM To tell them all to fuck off! There is a novel about a widow who can’t have another love affair because she’s mourning her husband. Then after some years she meets this gentle gynaecologist.

SPW Is this a joke?

JM No it’s a story I’ve read. Eventually they go to bed together. She’s nervous and he says “no no, it’s just vaginal dryness it’s a symptom of blah blah blah. We should use some lubricant.” He talks about the whole thing like a mechanic and so she realises she can’t fuck him. I knew a guy who had a shower after every time he had a shag. He was Czechoslovakian.

SPW Interesting. It’s a useful analogy for art criticism and the way artists talk about their work. I can’t bear art jargon. It’s an abuse of language.

JM It’s vile. It’s utterly vile.

SPW If I talk about any of my pictures I tend to resort to anecdotes or to contextualise them. That seems to be safe territory. I want to always avoid trying to intellectualise or justify them. Essentially, they are just pictures that you might have hanging on your wall. They might appeal to you, and they might not. Over-intellectualising art is harmful.

JM You know there are left brainers and right brainers. Curators are right brainers. They think linearly. They’re dreary logicians. Logic governs language because everything they construct in response to a work exists only in language. It’s written within the limits and parameters of language. They can’t say “this painting makes me feel yellow”, or “gooey”, because it doesn’t mean anything in language. It’s gobbledegook. So they have to rationalise it in language. If you are going to be successful in the art business you have to make curator friendly art. You’re a right brainer but you’re making work for the left brainers. You’re pulling art down to the level of commentators and journalists.

SPW You’re enabling it to be contained in sentences.

JM 75-95% of all art we see is in magazines and books. You rarely see real paintings. You see photographs of paintings. So paintings which reproduce well in a photograph are going to be more successful. Bad paintings photograph really well generally. Great paintings don’t come across so well. You know we can’t win. We’re in a business where we know we’re doing something right if we never sell anything. If your work’s any good it should never be reproduced. It’s better never to be written about because then your work is never reduced in any way. And so basically you end up like me: invisible and never written about.

SPW Yes. Well I’ve got that to look forward to.

JM We’re just fucked. We should take ourselves outside and shoot ourselves in the head.

SPW Maybe we should.

August 2013