HALFBOY

This project of work was originally exhibited at The Heong Gallery in Cambridge, UK from November 2018 until February 2019.

The exhibition will tour to Snape Maltings in Suffolk, UK (7-23 June 2019) and the School of Art Gallery and Museum at Aberystwyth University, Wales (7 October - 22 November 2019).

Alan Bookbinder

Foreword

An exhibition can often be either intensely moving or deeply thought-provoking. Rarely is it both.

For the ninth show at Downing College’s Heong Gallery, we present an intensely personal set of works by Stuart Pearson Wright that both move and question. Wright has a special connection with the College, as he was the artist commissioned to paint the portrait of Professor Geoffrey Grimmett, who recently retired as our 17th Master.

For this exhibition of works made between 2013 and 2018, Wright draws on often painful, or embarrassing, memories from his childhood and youth. He is not afraid to be frank or confessional, or to expose his own vulnerabilities. Here, the empathy for which his portraits are well-known, is turned on his own troubled family story. In particular, he addresses the void in his life that comes from not knowing who his real father is. Being the son of an anonymous sperm donor, he feels that half his identity has been denied him – hence the title, Halfboy.

In his conversation with Marco Livingstone, he speaks movingly of the distress of living with such an important question, to which the law prevents him from finding an answer. Being denied a father’s love, affection, and pride is the personal torment that inspires this show. It is tremendously moving to learn through these works how Wright’s tenuous sense of identity has disrupted his family relationships both as a child and as an adult.

Beyond this candid personal story is a broader controversy, explored with great sensitivity in Dr Ruth Curson’s account of her encounters with Wright and in Dr Alex Morris’ broader historical essay. The clash of rights between a sperm donor’s right to anonymity and a donor-conceived person’s right to trace his or her biological father is agonising. As with many other medical and technological advances, something may be scientifcally feasible, but it threatens to outpace our ability to process it ethically.

As Master of Downing College, I am enormously proud of the Heong Gallery’s impressive achievements. In a very short time it has become a beacon in the cultural landscape. We’re open to everyone and I encourage you to visit.

Alan Bookbinder is Master of Downing College, Cambridge.

Marco Livingstone

In conversation with Stuart Pearson Wright

18 September 2018. Suffolk.

ML Over what length of time have you painted all of these?

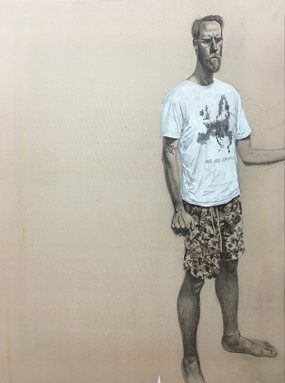

SPW I painted Stepdad in 2015.

ML When you painted Stepdad, did you already have in mind to make a whole exhibition from this theme?

SPW No, I wasn’t sure what I was doing at that stage. It started with a box of old family photographs I found. When I was a child, my mother and I moved around a lot. We left my first stepfather when I was six and led a nomadic existence for several years. She married Cyril when I was eight, seen here in Stepdad. Moving around so much meant we lost track of most of the photographs from my early childhood. The ones I have are valuable to me, particularly since I don’t know who my real father is. My sense of identity is tenuous.

ML Does this feel like a double gap? First of all, you don’t know who your biological father is, and, secondly, you are missing photographic evidence from that formative period of childhood.

SPW That was part of the instigation for making this work, to reassess my memories of my childhood and my ambivalent familial relationships. When my mother married my second stepfather, I was told that I had to call him ‘Dad’. I wasn’t allowed to use the word ‘stepdad’. I remember being told that I must refer to my older half-siblings as ‘brother’ and ‘sister’. This painting is called Halfboy and Halfsister, and there is another one called Halfboy and Halfbrother. Because these descriptions weren’t allowed, I attached feelings of confusion and guilt to the idea that my siblings were in fact half-siblings. It was like a sinister and unspoken secret. When asked ‘Do you have any brothers and sisters?’ I wouldn’t know how to respond, whether to include step-siblings, half-siblings or none at all. My understanding of ‘my family’ was confused.

ML So, was there a stepdad on the scene when you were born?

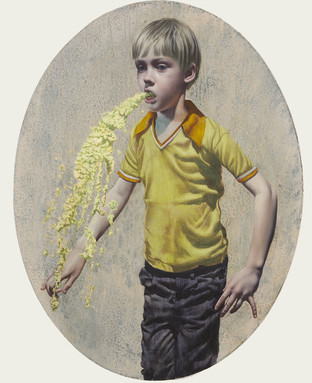

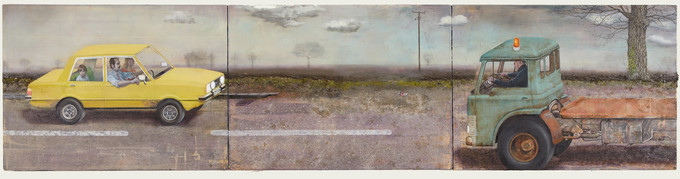

SPW Yes, Bob. He appears in the triptych called Nausea, which also relates to the painting of the boy being sick – they are parts of the same narrative.

ML You vomited because you were carsick? And, also, from a psychological nausea? Does Nausea link to a specific memory?

SPW I was about five and we were stuck at a petrol station. I felt sick with he smell of the petrol fumes and, to remedy this, Bob gave me a Kit Kat. We then drove to Debenhams, and I vomited all over the carpet there.

ML Why were you alone in the car? Had your older siblings already left home?

SPW Yes. Effectively, I was an only child. I wanted to revisit these memories with these works and also defiantly use the forbidden language of familial nomenclature. So, to call that painting Halfboy and Halfsister feels weirdly transgressive.

ML So, you are being disobedient when you are making a painting?

SPW I am. Ironically, the one thing that worries me is how my sister (or half-sister) will react to that.

ML Because she doesn’t want to think of you as a half-brother?

SPW And I don’t want to think of her as a half-sister either, and yet that is the truth of the matter. In denying the truth we are conspiring to define it as something unpalatable or wrong. I have recently become fiercely adherent to the idea of being truthful about things. The word ‘Halfsister’ also relates to the portmanteau ‘Halfboy’, which is the title of the exhibition.

ML And ‘Halfboy’ because you don’t feel complete, since you don’t know these aspects of your personal and family history?

SPW Precisely. I don’t know who my father is, because I was born via artificial insemination. I am denied half of my identity.

ML Do you wonder where your artistic talent comes from? That it might be from an unknown biological father?

SPW I’ve dwelt on that a great deal over the years. My mother paints, but the likelihood is that my father was probably a medical student at King’s College Hospital, because that’s where I was conceived.

ML Is it now legally possible for you to find out?

SPW No. The law was changed in 2006, but it wasn’t retrospective.

ML Does this upset you on a regular basis?

SPW Profoundly.

ML And has it all through your life, even though you have not dealt with that theme in your paintings before?

SPW It has done. When I was eighteen, I believed I might be able to find some information, but hit several dead ends in my search. That was devastating.

ML What would you hope to find out? Do you just miss a feeling of closure?

SPW If someone has died, there is a natural process of grieving that takes place. In my situation, there isn’t any kind of closure available. There’s always just a big question mark.

ML One could say that not knowing has given you this incredible subject and it has fed the intensity of these paintings. If you were a happy person, with a conventional family background, you would be a different kind of artist. But there is an atmosphere of impending doom in your work. Perhaps it was destined to come into your work, and you should embrace it?

SPW Listening to Amy Winehouse’s music now is inseparable from the retrospective knowledge of the tragedy of her life. That imparts a sense of pathos to the songs which is compelling for us as the listener. But how did that feel for Amy Winehouse: to live through that profound sadness and tragedy at the time? Were the songs a price worth paying?

ML Would you rather not have had this background and not painted these pictures?

SPW Definitely. I just want my father, and I want him to be my father. I don’t just want to establish my inherited identity, I want my father to give me a cuddle, and tell me that he’s proud of me. I want to be loved. I’m denied that. If you’re conceived by donor insemination, you’re taught that you should refer to your father as the sperm donor or just the donor. I refuse to do that. Doctors are unnerved because the word ‘father’ has a specific set of family connotations, but this man is my father and it is my right to call him that.

ML The weird thing is that you’re still young enough that your biological father could well be my age. I’m twenty-three years older than you.

SPW You weren’t in Kings College in 1975, were you?

ML I have never been there! And whatever you do, please don’t call me ‘Daddy’. There is still, in theory, a lot of time and you could find him.

SPW And not just him: Grandparents, more half-siblings: their names, stories and histories, where they were from. I have none of that. It creates a bottomless sense of sadness and a void in my life that I battle with. It has reached volcanic presence in my life, taking me almost to a tipping point over the last few years.

ML Has that got worse since you had children?

SPW I was telling my seven-year-old son about the fact that I don’t know who my dad is. He gave me a cuddle and said, ‘I’ll be your Daddy’. That’s probably the most touching thing that has ever been said to me.

ML I have friends who were adopted who are in a similar place, and are psychologically troubled by not knowing their birth mothers. So your situation sounds unusual, but there are other people experiencing similar things who will relate to these paintings. Let’s look at Nausea. It’s striking that the middle panel is unpopulated – there is a vacancy in the middle that is clearly not accidental.

SPW There was a moped rider there originally but it didn’t work having someone in the middle panel. I wanted the space to be empty.

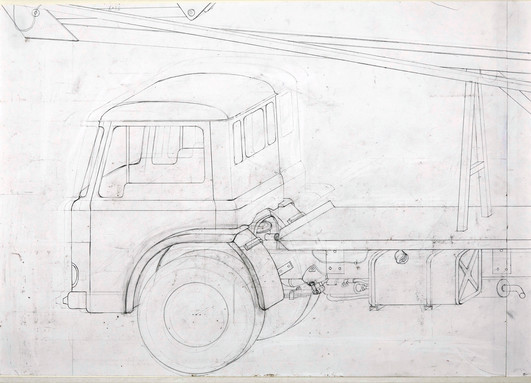

ML Is the lorry a part of the memory of the actual car journey?

SPW No, they are non-specific. I was just feeling nauseous in a car. That is the extent of the actual memory.

ML You say that they are non-specific, but everything is delineated with hallucinatory detail. It feels like you are recalling – dredging – this from somewhere in buried memories.

SPW There is a degree of invention, combined with the memory.

ML So, you did that for pictorial reasons, but there is also an erasing of memory going on. And this very barren landscape behind, does that refer to a particular place?

SPW No, the event took place in Sussex but this is a Suffolk landscape. I’ve come to realise that it’s liberating not to have to be objectively accurate in a narrative painting. This is more about evoking a subjective feeling than depicting an actual journey.

ML And the gaze of the boy out of the painting? He’s very detached from the parents in the front seat, lost in thoughts – terrible melancholy in that face. You’ve always had this extraordinary technique, almost like a miniaturist, which I realise you have had to fight against – for that not to take over – and so I like the loose, abstract passages of painting. That central panel seems key. That represents the gap in memory and the gap between what you can reconstruct in your mind and what you can reconstruct in paint.

SPW I love experimenting with paint and collaging other materials. The grass is made from the stuff that model railway enthusiasts would use to create their landscapes. There’s a tree on the right, where I have cut each of the ivy leaves from paper with a scalpel and stuck them on. Similarly, the rusty surface on the lorry is a section of plastic tread-plate used in architectural models. The pattern is flat to the viewer and thus works against any linear-perspectival reading. I flatten the picture plane by tilting it up theatrically. Although, in isolation, the objects and figures are rendered very naturalistically, I’m employing a perspective system that distorts, and creates a sense of conceptual distance.

ML It’s what you’d see in a Japanese nineteenth-century woodcut, where the pattern doesn’t follow the folds of the cloth. It’s almost like you are looking at a fairground mirror.

SPW Everything in Nausea is rendered in isometric perspective: all of the diagonal lines are at 30 degrees to the picture plane. Isometric is a perspective system that one would normally associate with an architectural drawing. When I was working on Nausea, I had been spending a lot of time making LEGO with my son. If you continued building LEGO you could create an entire universe. You just have to follow the rules of the system. I wanted to create that feeling with this painting by applying a system to it.

ML Where does that perspective lead the spectator?

SPW Not in a real space. We are elevated and looking down on a theatrical space where the ground plan is like the raked floor of a stage: observing the scene through a proscenium arch. The theatricality and artificiality of the scene is manifest and deliberate.

ML In Halfboy and Halfsister it’s almost like descriptions of people having out-of-body experiences; floating above the space and seeing themselves. Was that an intentional thing you were doing?

SPW Very much so. I visited Norwich Cathedral as a student. In the roof bosses there, the artist has had to convey a biblical narrative in the simplest form possible, so in the Last Supper, the table is flat to the viewer and the figures are upright. When I saw these bosses, I had a eureka moment. I realised that I wanted to leave naturalistic perspective behind. At the time, I had been thinking a lot about Bertolt Brecht and his ideas of distancing effects or Verfremdungseffekt. I was interested in the idea that you are not trying to convince the viewer they are witnessing something that is real. You are embracing the artifice of the process. Figurative-painting is unavoidably a narrative form and telling stories is an inherently theatrical process.

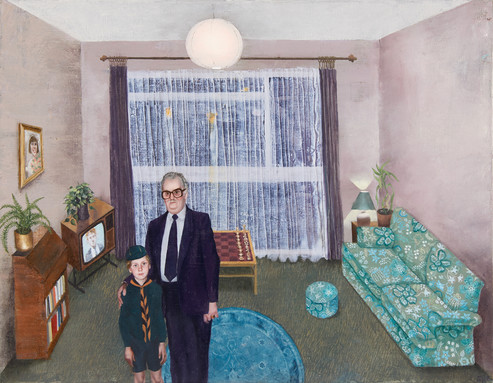

ML It can’t be lost on you that some of the terms of you use – ‘figurative-painter’, ‘narrative’, and ‘theatrical’ – are words that would frighten a lot of painters. You’re deliberately including them. The image on the TV that you chose is Cilla Black’s Blind Date. The potential partner is missing in that image. Is that why you chose the programme?

SPW Blind Date was always on the television through my childhood and my mother made me audition for the programme when I was 17. The television in the painting needed to be chromatically bright and the colours in Blind Date were always vibrant and saturated. I was trying to liberate my palette from the stodgy, dark colours I often use. Also, Blind Date has such wonderfully kitsch associations to the 1980s.

ML Can I ask you about some of the artistic precedents behind what you do? This plant reminds me of Lucien Freud’s Interior in Paddington, 1951.

SPW That’s one of my favourite paintings…

ML And then the Constable Haywain and the way that you paint figures somehow relates to Freud’s early ‘50s works. Is that coincidental?

SPW No. Early Freud is one of my main influences. Also, the artists who influenced Freud, like Graham Sutherland, John Minton, and the other English neoromantics. The Haywain is a reference to the fact that I am working in Suffolk.

ML It’s not that you had a reproduction of it in your childhood home?

SPW This isn’t an exact reproduction of the room in which I grew up. Although this is the sofa that we had at the time.

ML How have you reconstructed the pattern on that sofa?

SPW That’s from old photographs. It took weeks to paint that pattern.

ML You are using this technically laborious technique with very fine detail, and then the smoke from the cigarette is just glued-on sheep’s wool, in contrast to the approach that dominates the rest of the picture.

SPW Well, I enjoy that juxtaposition of techniques – the contrast between highly detailed rendering and something that is flat and abstract, again juxtaposed with something that is collaged and not made of paint at all. The TV is created with real zebrawood veneer stuck onto the canvas and Frenchpolished. With the wool, it seemed appropriate to use a material that is ephemeral. The textures are important. I was trying to recreate woodchip on the walls. My childhood was spent in rooms covered in woodchip. I tried to buy real woodchip to stick on the canvas and discovered that ironically they don’t actually make woodchip with wood-chips anymore! So, I made my own by flicking paint at the canvas with a toothbrush.

ML There is a lot in these paintings that draws the eye to the surface of the canvas. Halfboy and Halfsister is almost too unbearable to look at, at times. You need to have your eye distracted by details – the TV screen, the family photographs, the painting on the wall, the plant, and its shadow, which becomes almost like a figure itself.

SPW I want to reward people who get close to paintings and examine them.

ML There is a lot of art now that exhausts itself at a glance. To build so much variety of surface and technique into a painting brings you back to it, and allows you to re-experience it and notice different things. You could live with Halfboy and Halfsister for six months and suddenly notice something

that had escaped your attention before.

SPW Then I would feel that I had done my job well. This painting took hundreds of hours to make: one reason why the collection of works in the exhibition is smaller than I intended. I wanted to make around twenty paintings, of this size.

ML Can you foresee making more work after the show has opened? Is the theme exhausted for you?

SPW It is far from exhausted, but I will have to leave it aside to paint some commissioned portraits. I have to earn a living.

ML How do you imagine the experience for the spectator? These are extremely personal works. I am responding to them strongly and assume other people will also.

SPW I haven’t really stopped to think what people will think of these or how they will approach them. This painting, Up the Downs; A Teenage Tragedy of Erotic Ineptitude, is particularly personal.

ML This has a Pre-Raphaelite association. Millais’ Ophelia comes to mind.

SPW This was a maddening painting to work on. It took months. I felt increasing pressure to finish it because I had a lot more paintings to make. It’s not a painting that I ever ‘finished’ as much as ‘left behind’ in order to move on to something else.

ML It is an extraordinarily frank image. You are exposed, very literally, but from your point of view probably no more so than the psychological exposure of the paintings of you as a little boy.

SPW I started talking about this painting because you asked about my feelings towards other’s reactions to these paintings. This is the one painting where I began to consider that I was ‘putting something out there’ that is very frank and confessional, very of our time – an age where people post very revealing images of themselves on social media. This painting is the love-child of Instagram and the Pre-Raphaelites, you could argue. And there is a reference also to Nicholas Hilliard’s Young Man among Roses in the melancholy pose of the young man and the juxtaposition of the figure with the spiky brambles.

ML I imagine that, if a viewer were left alone with this painting, they would spend a lot of time looking at it. In a public space, a lot of people won’t want to be seen to be obsessing about the naked body. It would make them feel too voyeuristic.

SPW It’s a difficult painting in many ways – technically difficult to paint, and it makes uncomfortable viewing for me because it alludes to a painful memory. It is set on the Sussex Downs but the stream is an invention. Any self-respecting Sussex farmer will tell you there are no streams on the high grounds of the Sussex Downs. The landscape around the figures is drawn from local Suffolk locations, but again, the historical element is subjugated in favour of conveying a psychological state.

ML May I be so indelicate to ask, is this representing your ‘first time’?

SPW It is representing an attempt at a ‘first time’ which went horribly wrong. The condom was taken out with intent, but not properly used. This represents a holiday romance with a young language student from Austria. She was only in town for two weeks. I decided to take her for a walk up the Downs and attempt to lose my virginity with her. I was painfully shy and it was an intensely hot day. Neither of us knew what to do or how things worked and, because it was so hot, there were some very strong bodily odours. It was a scene in which things didn’t happen as intended. It was all very embarrassing.

ML You do have a dejected expression on your face and she is looking into the distance, thinking that this wasn’t such a good idea. I feel like I am intruding into sessions with your psychoanalyst.

SPW It is a bit like that. To return to your question of whether or not I’ll continue with these works once the exhibition has started: I need a break from this level of introspection that I have been engaged in for a long time. It will be liberating to move away from delving into my own memories.

ML It must be quite difficult for your wife to be with you when you are going through this.

SPW It is difficult for my wife, generally, just being in my proximity.

ML How much symbolism is in this painting? There is a dangerous feel to the thorns.

SPW That is deliberate; the juxtaposition of the naked bodies with spiky plants. I wanted it to feel like a threatening place; hostile nature and also the human detritus lying around. I wanted to create the sense of things lurking in the undergrowth that could cut, scratch, and contaminate the human body. And, yet, there are elements of paradise: a beautiful landscape despite all the bits of rubbish lying around. I can’t see a bucolic scene without expecting some human element to ruin it. In a perverted way, I’d enjoy going around the National Gallery and painting discarded tin cans, and condoms, and crisp packets in all of the Constables. Humans always destroy the natural world. We are like a plague on this planet. Up the Downs is a painting I had to make but I’m glad it’s behind me. It’s a key painting in this exhibition, although it doesn’t sit well with the other paintings, stylistically.

ML It relates to things you have made before, though. Some of your earlier paintings have an Otto Dix air to them, which survives in this one.

SPW It does relate very clearly to a painting I made around 2002: Domestic Scene, and a subsequent piece called Second Domestic Scene, a large drawing. In those two pictures, I took myself as the subject and created episodes from a visual diary, inspired by the work of Bonnard and his domestic scenes.

ML When you chose that title, were you aware that Stanley Spencer had done a whole series called Domestic Scenes and Hockney as well, in 1963.

SPW I certainly remember the Hockney ones. They’re wonderfully ironic.

ML They also have, in common, a very selective use of objects in an otherwise empty space. Hockney talks about how, when you enter a room, you notice particular things according to your own interests and obsessions. There’s a selectivity of vision, which you are also using in your paintings: every represented object has been deliberately placed to attract your attention. There is nothing that is random. Things have been filtered out in the memory you are conveying. In Stepdad, there are more objects but they all seem necessary. There is a painting on the wall…

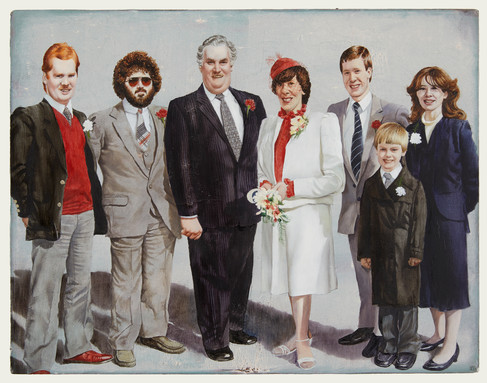

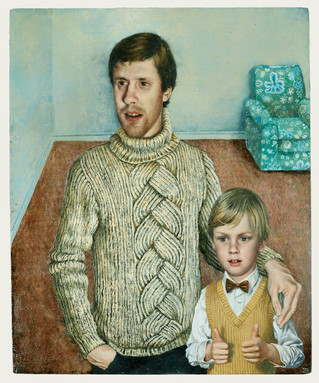

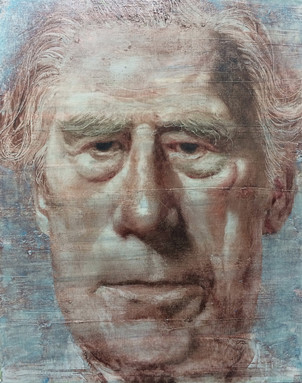

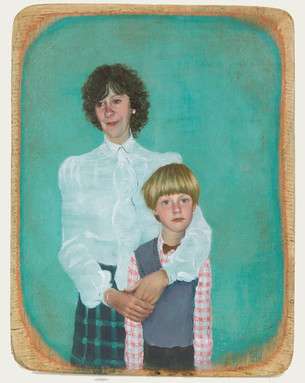

SPW That image on the wall in Stepdad is supposed to be a photograph of my sister-in-law, my half-brother’s wife. There is a painting of that same photograph called The Happiest of Days. I’m interested in the way people pose for photographs. Several of the smaller paintings in the exhibition are lifted directly from photographs, but are in some way exaggerated. I’m not interested in accurately recreating a photograph per se but in presenting people ‘in the act of posing for a photograph’. This painting is called Halfboy and Halfbrother. This is a weirdly painful picture for me, because I have strong feelings of disappointment and sadness towards my half-brother. He is twelve years older than me and we’ve always had a difficult relationship. What interests me about this tender pose is that it represents a lie for the camera: people pretending to have a loving relationship.

ML He is putting his arm around you in a protective way, as a father might. Why were you dressed up like that, with a little bow tie?

SPW There are lots of photographs of me as a child in which I am wearing a bow tie. I think that is partly because we didn’t take photographs very often. We were a working-class family and photography was expensive in those days. The camera was pulled out at Christmas time and when people were visiting. I was also a dramatic little boy.

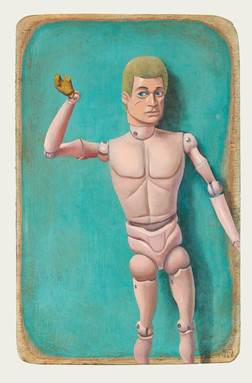

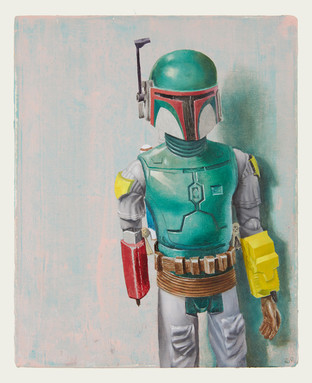

ML These still life paintings represent toys you had at the time?

SPW Yes, some of which I still have. The teddy bears I had as a child. I used to always eat Monster Munch and I used to have lots of Action Men. The one in this painting has some of his fingers missing. All my toys were second-hand because we were poor. I wanted to paint toys that were broken. The Action Man is a kind of self-portrait in that respect; he has become Inaction-Man, analogous to Halfboy.

ML What about this painting based on a group photo?

SPW This is called Halfboy and Mother, Stepfather, Halfbrother, Halfsister and Stepbrothers.

ML Is your mother still alive? Do you see her?

SPW Yes, she lives locally. My mother would have been an artist herself if she hadn’t lived such a challenging life. She is incredibly supportive of my work.

ML She is not disturbed by you making all this work that reflects on her life as well?

SPW I don’t know. She hasn’t said so, although it is odd showing a picture like Up the Downs to my mother. I’m happier showing that to strangers than people I know.

ML It will make people uncomfortable because it brings out the anxiety we have about ourselves – our body image and our sexuality.

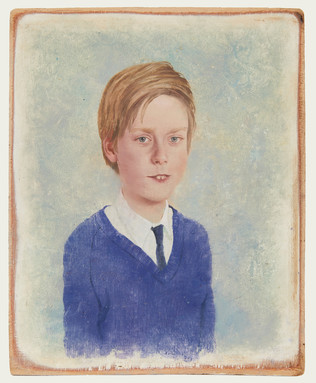

SPW And yet, Up the Downs is also a humorous painting. I can’t avoid making my paintings humorous even when they are disturbing or tragic. This one is called The Loneliest Boy in the Whole Fucking World. It is set in a council estate in a village called Flackwell Heath. We moved from that house forcibly when my Mother’s agoraphobia prevented her making the return journey from Sussex to Buckinghamshire. I never got to say goodbye to any of my friends.

ML Sounds like my childhood. My parents were constantly moving to different countries. It makes people leave horrible loose threads. The space in the painting is so constricted – almost like a cell. The garden is very tight and compartmentalised.

SPW It’s a tiny theatrical space. I found several faded photographs of this front garden, which I used as references. I was trying to recreate the desaturated colours, thinking a lot about how photographs and memories deteriorate over time. These muted colours create feelings of nostalgia and evoke sad memories of a melancholic childhood.

ML Some of the other paintings – the family group portrait, especially – have this feeling of playing ‘happy families’ and pretending everything is alright through the details like the happy little flowers. But there’s a sense that something is lurking behind the curtain, and you desperately clutching a C3PO figure, all of which undermine the jolly garden. What you are doing in these pictures is tricky: not to overload the symbolism or direct the viewer too much, but to provide enough visual evidence for people to concoct their own narrative; to leave it open enough to respond to.

SPW I’m compelled to paint the terrible architecture of these 1960s council estates with their identical little two-bedroom houses and little gardens, like a LEGO city.

ML Here we are, in your studio, and the incredible house you live in now and you are thinking back to your childhood and the kind of environment where people would be subliminally taught to have no hope about their futures. When did you begin to have aspirations to be an artist?

SPW From around five or six. I loved drawing, being, effectively an only child.

ML Knowing that places a different spin on this painting for me – that you’re going back to a point in your life where you had already begun to imagine yourself as an artist; an unhappy period. Yet, that was the beginning of your escape from it. You are representing your origins as an artist, not just your origins as a human being.

SPW I hadn’t thought of it like that. I think I was trying to come to grips with the origins of my psychological state, as someone who is inherently melancholic and has experienced depression and anxiety. I wanted to trace the origins of these feelings in my boyhood. It is impossible to make these sorts of paintings and not talk about one’s mental state, by way of explanation. This was really just a painting about feeling lonely.

ML Can I ask you what you feel about outsider art, which in so many cases responds to psychological trauma. Do you feel a connection with that kind of art?

SPW Definitely. I discovered a Canadian Inuit artist recently, Annie Pootoogook (d. 2016). She made extraordinarily moving drawings of her life: subjects like domestic abuse and sex. The wonderful thing about her work is the details of the room and what permeates all of the details is a sense of common, shared humanity; sadness, joy and humour.

ML The thing that characterises a lot of outsider art is that it is made out of necessity, not for public consumption, to be displayed in galleries or sold. Your work shares characteristics with outsider art, yet is for public exhibition. You share this quality with other artists I appreciate like Paula Rego. A lot of her work emanates from childhood memories. She says that when she feels ashamed of other people seeing her work, she knows there is some truth and authenticity to the work.

SPW It’s no accident that this body of work is being created for a public gallery, as opposed to a commercial gallery. It’s liberating to make pictures purely to be exhibited, not to be sold in a commercial space. I can’t imagine anyone would ever buy Up the Downs, but nevertheless, it had to be painted.

ML Let us turn to this big painting that you are working on now…

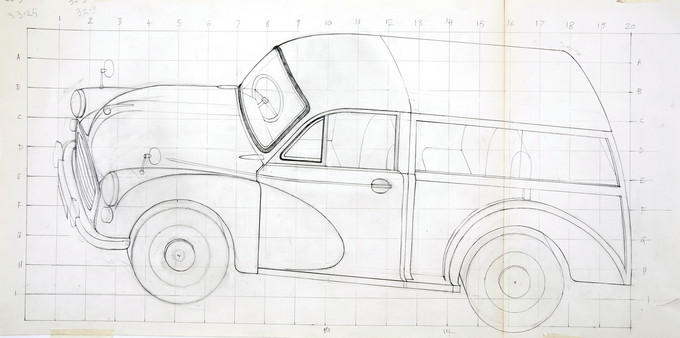

SPW Is going to be called Kid with a Bleeding Brain. There is a technical drawing next to it on the wall, which tells you what is going to be in the painting. There will be a boy walking up the road, his head bleeding.

ML Is this how you work? You make an elaborate preparatory drawing?

SPW Not always, but I had to work in that way for this painting because of the technically difficult perspective system.

ML How do you transfer the drawing to the canvas?

SPW By measuring each distance and scaling it up on the canvas. It is an absurdly longwinded way of doing things. I was playing on a roundabout and some bigger kids spun it around really quickly. I flew off, landed on my head and cracked my skull. When I recount this story to my mother, we disagree how long I was in hospital for. She claims I was there overnight, while I believe that I was there for two weeks. My mother is probably correct, but, from a subjective point of view, I was there for ages. It says something about how childhood memories and emotions become distorted or enlarged over time.

ML The kinds of spaces that you are depicting are dreamlike. When you try to describe a dream to somebody else, there are lots of incomplete things and they don’t make rational sense. That’s how these paintings work.

SPW Because most of it is invented, although I did return to the street where this happened: a council estate in Bexhill, and took lots of photographs of the houses and playground.

ML There’s the little child wearing Lolita glasses over here.

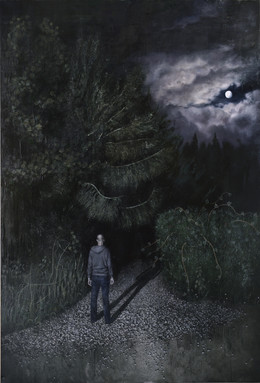

SPW That’s my daughter Theda. I don’t know how that painting relates to the others. I figured that this collection is about my family history. History is not just about the past – it is an ongoing process. My daughter is a very significant part of my story. Reflected in her sunglasses is a little self-portrait. I’ve also got a portrait of my mother, as she is now. I needed to bring the present into this history. I have included some other paintings which were made prior to beginning the Halfboy series. This one is called Wanderer, a reference to the Caspar David Friedrich painting. I painted these around 2014, shortly after we moved to Suffolk from East London. It was a bleak time; my wife had a miscarriage on the day that we moved. I was deeply depressed for a year at least. It’s no coincidence that these paintings are all incredibly bleak and dark. We both felt very isolated and out of our depth. When two people are feeling depressed, although they might be in a similar place, psychologically, it is very difficult for them to connect.

ML The sad truth is that your misery can become someone else’s entertainment. These are very powerful paintings. They are testament to your honesty.

SPW The reason I wanted to include these paintings in the exhibition was that, although they are not strictly self-portraits, I was trying to convey my psychological state. In Martinmas Time, you have these two figures looking in different directions, both surrounded by dark clouds.

ML Why is there a caravan?

SPW When we first came to Suffolk, I didn’t know what kind of work I was going to make or how I was going to respond to being here. I drove around looking for scenes I could connect with, within the landscape. I realised very quickly that I wasn’t drawn to pretty woodland scenes. Every farm has an area where the farmer shoves all his rubbish, often with an old caravan. I asked a farmer if I could paint this one. The irony was that, ninety degrees to my left, was a beautiful Suffolk scene.

ML Curiously, it does anticipate some of the later paintings about your childhood. A caravan suggests a nomadic existence and homelessness.

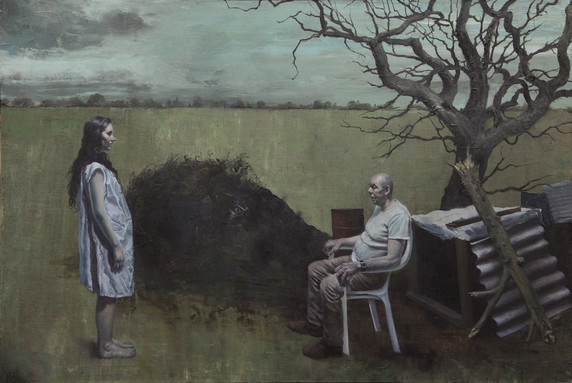

SPW Yes. Wheateaters began with that generic white plastic chair. Why would someone have left it next to a clump of matter, a piece of corrugated iron and an old oil drum? That question prompted the painting. I had to make a painting of someone sitting there. Afterwards, I decided that I wanted another figure and asked my wife to pose. Then it became an ambivalent confrontation between two figures. In contrast to the Halfboy paintings, there are no given narratives here. Viewers impose their own narrative on them.

ML The spiky tree in Wheateaters is sinister. People who live in cities, who don’t necessarily want to live in the country, tend to romanticise the idyllic aspects of country life. They tend not to think about all the abandoned, rusting farm machinery and other crap that you do see in the country. You moved here and presented a rather bleak vision of country life, although it has its own beauty too.

SPW That was the thing I was drawn to. Wanderer is set in our overgrown car park. There was something about the image of a man gazing up a dark and unknown path that I connected with.

ML The Friedrich overtones and the sense of the unknowable are very strong and deliberate. It also makes me think of Schubert’s Winterreise, the wandering alone in nature and contemplating your mortality. There is also the issue of prophetic fallacy. If you go to a funeral, and it a bleak, stormy day, then you think nature is responding to the death. If you have a beautiful, sunny day, you think, ‘Oh the irony!’, that life continues. Whatever is happening in nature, you will connect to your mental state.

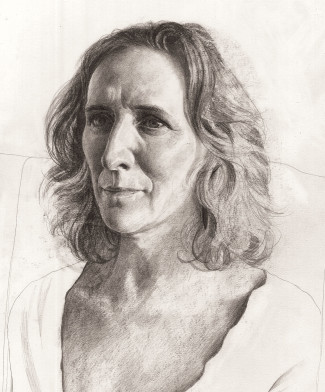

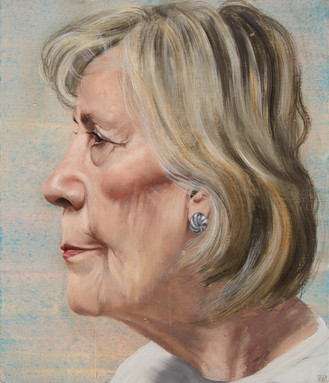

SPW It is true of portraits as well. When I am painting a portrait, I always impose my own melancholic self-image on the sitter. I once got into a heated public debate about portraiture with Maggi Hambling. She asserted that she was trying to convey a sense of the subject’s soul and I said ‘Actually, what you are trying to do, Maggi, is find yourself within your subject. You are painting the element of that person that reflects your self-image and, therefore, the bit that you understand and connect with.’ I said to Maggi: ‘All your portraits are self-portraits.’ You’ve only got to look at her sculpture of Oscar Wilde – the camp gesture of the hand holding the cigarette, that’s Maggi Hambling as Oscar Wilde. It’s like a fancy dress party. There is a Jorge Luis Borges quote:

‘A man sets out to draw the world. As the years go by, he peoples a space with images of provinces, kingdoms, mountains, bays, ships, islands, fishes, rooms, instruments, stars, horses, and individuals. A short time before he dies, he discovers that the patient labyrinth of lines traces the lineaments of his own face.’

ML If you are making a portrait and you are just recording the features, then a photograph might do it better. If you are responding to them and trying to find what your connection is with them, then you are in it too, naturally.

SPW Exactly. That is the problem with so many contemporary portraits. The artist might be very good at doing an ear or a nose, but there seems to be little connection between artist and subject. The photograph as a source for the painting (as opposed to painting directly from life) has served to break down that connection. The contemporary portrait is often little more than a demonstration of technique and thus leaves us cold.

ML Do you have to like the person you are painting?

SPW Not necessarily, but you have to find a connection.

ML Anyway, you have moved away from being ‘just’ a portrait painter.

SPW I have pushed my work into no-man’s land: somewhere between portraiture and semi-humorous, existential narrative figure paintings.

ML But you could have had a very comfortable career just making portraits?

SPW Yes, but it would have been too restrictive. I still make portraits, both commissioned and ones that I instigate, but I have always felt ambivalent towards portraiture.

ML I don’t think you would have felt satisfied. The imaginative dimension is hardly possible to express in portraiture.

SPW I was always trying to shoehorn that in. That was the element that troubled people who commissioned work.

ML Squeezing it into a portrait might have looked contrived and wilful, whereas, in your own work, you are allowed.

SPW For my part, the best portraits are first and foremost works of art and portraits second.

ML This is the problem with any collection like the National Portrait Gallery, that the quality of the art can become subservient to whether it is a good likeness or not. But that’s not a reason to abandon portraiture. When you think of Cranach or Dürer, some of their best paintings are portraits.

SPW Very much so. You could say that about lots of artists. Think about Rembrandt… Shall we go and get some lunch?

Marco Livingstone is an art historian, writer and independent curator.

William Feaver

Stepping Back

In retrospect things seem smaller, details intensified and gripping. This gives a painter such as the inimitable Stuart Pearson Wright a peculiar authority or at least some sort of access to the minutiae of memory. We all have our childhoods and many of us produce novels about them but for the painter early visual impressions have a peculiar significance never really outgrown. Which is what makes these views, scenes and items so telling.

Stuart is a great one for the slightly skewed. His pictures of himself are apt to be caught up in worrying considerations. Is the pose credible? Does the cap fit? He faces exposure to enquiry. What is it that demands such attention? Why the distancing? Why the exactitude?

The answer has to be that memory is so selective it pays to cultivate only what most readily springs to mind. Hence the combo of pullover and bow tie, the spattering of floral motifs on armchair and sofa, the serried brickwork, the vomit, the wedding photo smiles, sandals and loafers, and the well disciplined lawn.

Moreover - and there’s always a sense of more to come in compositions such as these - the preoccupations laid out are titivated to a high degree. The lungful of cigarette smoke exhaled by an elder sister is all the more repulsive for being rendered in raw wool. Similarly, to spew bilious yellow is to create something of a first in visual repertoire.

Questions arise. Who, in this Toy Story 2-esque set of circumstances, can distinguish between the actual and the graphic? The Monster Munch packet, so redolent to any child of the Seventies, becomes a thing of monstrous memorability. To The Loneliest Boy in the Whole Fucking World, a brace of garden gnomes may prove to be more companionable than the repro C3PO. We peer in, like the human pre-teenager in the TV adaptation of The Borrowers, to find under the floorboards a netherworld in which Ian Holm, titular head of the Clock family, exercises the pettiest of tyrannies. Then comes Up the Downs, a painting deliberately designed, surely, to play up to Holman Hunt’s rural seduction scene The Hireling Shepherd. Only here the sap fails to rise and latter-day Pre Raphaelitism gets a smack on the wrist

Holman Hunt got religion and Millais went tepid. Stuart Pearson Wright shows no signs of heading towards either such fate. There is Mannerism, yes, and the loving cultivation of what is worth remembering, the one great lifelong concern.

William Feaver is an art critic, curator, artist and lecturer.

Stuart Pearson Wright: A Portrait

by Dr Prerona Prasad

Unusually for an artist, Stuart Pearson Wright (b. 1975, Northampton) can pinpoint a single work that he considers his favourite painting – The Crucifixion by Early Netherlandish master painter, Dirk Bouts, now at the Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique. Christ and the two thieves are raised up on tall crosses above the assembled crowd, not on the top of the hill at Golgotha, but in a riverine plain set against a backdrop of an imagined landscape of hills, within which nestles a decidedly medieval Jerusalem. Painted in glue tempera on linen, a support Wright himself prefers, the painting is bustling with characters in costume contemporary to the painter, rendered in rich, dramatic colours, of which the reds and deep blues are the only ones to survive the ravages of time. What finds greatest resonance in Wright’s own practice is the tableau of human reactions in evidence in the gathered crowd. Despair, resignation, morbid curiosity, and indifference are picked out delicately in white chalk, the brilliance of the medium fixed in glue. In this, the most sombre scene in Biblical iconography, the viewer is invited to find a mirror for his or her own emotions in the assembled crowd, rather than find targets of veneration or hatred.

It is for his own empathetic rendering of subjects, that Stuart Pearson Wright is best known. Handed his first box of oil paints by his mother at the age of fifteen, Wright received early commissions for portraits from colleagues at summer jobs. Admission to the Slade School of Fine Art in 1995 allowed Wright the physical space to be an artist, but the rigours (some would say, drudgery) of a traditional fine art curriculum had long since been deemed inessential. Wright’s training, therefore, came from the close study of Old Master paintings and the figurative paintings of artists like John Minton and Lucien Freud. One of the few working-class students at the Slade, Wright’s desire for success was underpinned with the anxiety that there would be no Plan B nor financial safety net for him. Always the last to leave the studio, Wright recalls hiding under the worktables to evade patrolling guards, and was nearly expelled for ‘breaking in’ on a Sunday to collect his own paintings. In his third-year, with no money for rent, Wright lived in a parked van in Primrose Hill for a term, conducting his morning ablutions while watching the celebrity residents of the locality on their jogs.

Luckily for Wright, the National Portrait Gallery (NPG) provided the young figurative artist an avenue for showing work through the BP Portrait Award competition. In 1998, Wright won the travel award, which allowed for his series From Eastbourne to Edinburgh, a Painter’s Odyssey to be made and exhibited both at his degree show and at the NPG. He was heralded ‘a Hogarth for our times’ by Godfrey Barker of the Evening Standard and his first major sale was Tisbury Court 1999, A Tragicomedy, from the series. A further turning point came in 2001, when Wright won the BP Portrait Award for Gallus Gallus with Still Life and Presidents, an imagined tea party attended by six presidents of the British Academy. In a composition that is reminiscent of the ceiling bosses at Norwich Cathedral, the sitters gaze purposefully in all possible directions but at each other, their thoughts occupied by greater concerns than the raw, plucked chicken that is the centrepiece of the table. The award resulted in a commission for a portrait of the writer J. K. Rowling. As a painter of people as well as a jobbing portraitist, Stuart pursued sitters who intrigued him, which extended to ambushing John Hurt on Old Compton Street and convincing the actor to allow Wright to paint him. A series of such portraits of actors were brought together in Most People Are Other People, an exhibition at the NPG in 2006.

For an artist, whose critical and market success has been closely linked with portrait painting, Stuart Pearson Wright has an ambivalent relationship with the genre. He has always been interested in depicting character and conveying a sense of what makes a person, but is not convinced that ‘straight’ portrait painting serves an essential role at a time when high quality image-making is available to anyone with a smartphone. In 2008, he took a sabbatical from painting portraits to focus on other projects. His painting Woman Surprised by Werewolf was shortlisted for the John Moores Painting Prize and Wright was invited by Riflemaker, London to exhibit new work in 2010, 2012, and 2013. The first of these exhibitions, I Remember You, comprised portraits of Wright and his associates in settings from the American West, often painted onto found canvases of landscapes. Together in Electric Dreams, 2012, and Love and Death, 2013 were wider explorations of life, sex, and mortality, which occasionally overlapped with Wright’s personal history and memories. Wright also made forays into film, set design, music, and sculpture.

With Halfboy, Stuart Pearson Wright is both artist and subject, with memory and grainy childhood photographs serving as inspiration. We follow Wright’s childhood in non-descript suburbia and meet a shifting cast of family members who tell the story of the young artist’s feelings of loneliness and rootlessness growing up. Pathos collides head-on with bathos, with humour and playfulness inserted into even the most uncomfortable and stomach-churning of scenes. There is no hierarchy of significance, with well-worn toys, grave physical injury, and episodes of crushing embarrassment all given the same painterly attention. For Wright, they are all equal in reconstructing an ordinary life made extraordinary in the telling.

Dr Prerona Prasad is Exhibitions and Programming Manager at The Heong Gallery, Downing College, Cambridge.